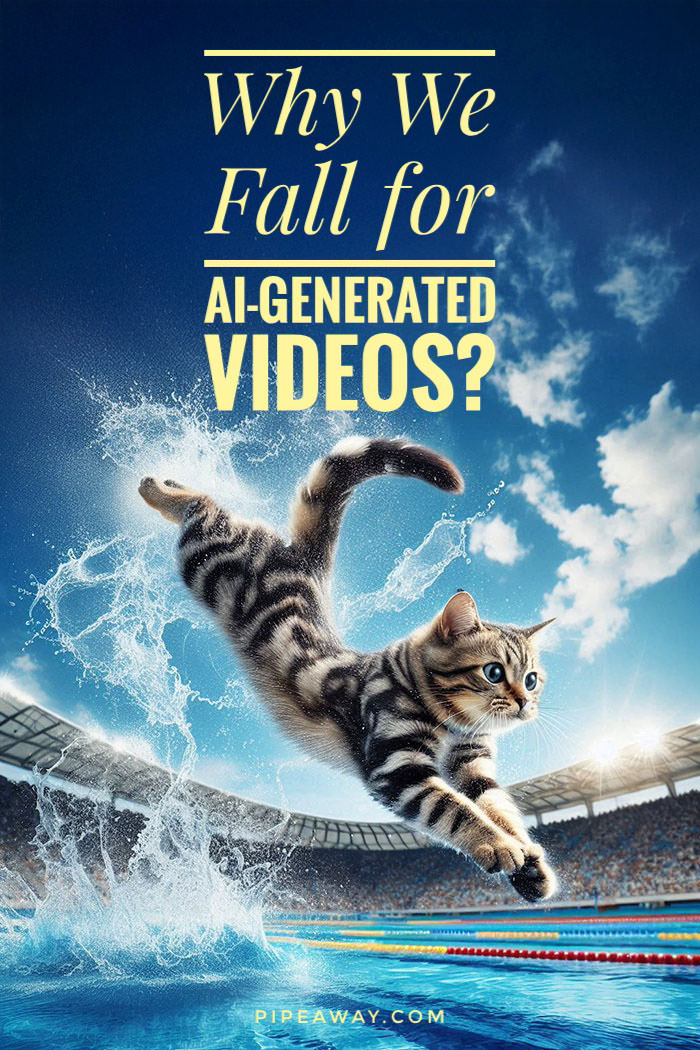

It’s absurd. A fluffy Maine Coon struts down a diving board, somersaults into the air, and slices through the water with Olympic-level finesse. Welcome to the Michi Olympics, where AI-generated cats compete in high diving! The internet is obsessed. Despite being generated by artificial intelligence, these feline athletes racked up tens of millions of views across social media. Enthusiastic fans were wowed by the “impressive display”, they applauded the cats’ bravery, and the most curious one asked: “How did they train them?” Are we truly losing the ability to tell fantasy from reality… or are AI-generated videos simply prompting us to do what humans have always done when faced with dazzling new technology: fall for it?

There’s a sucker born every minuteP.T. Barnum

Cats were among the first social media stars to break the internet. Since Charlie Schmidt uploaded his “Keyboard Cat” to YouTube in 2007, the viral video has amassed more than 2 million likes.

But when, last week, Pablo Jiménez prompted Hailuo 02 (an AI model by China‘s MiniMax) to generate a Cat Olympics reel, pool-diving cats collected nearly 10 million Instagram likes in just five days!

The newest trending meme showed that cats still rule the web, but it also reaffirmed P.T. Barnum‘s alleged theory that “there’s a sucker born every minute”.

“No way, they are better swimmers than me”, one awestruck commenter said.

Naturally, Dog Olympics followed the viral trend shortly after. A worried animal lover pleaded: “But why do dogs and cats do this??? Respect their nature, not your ambitions!!!!”

There was even a detective mind who didn’t find it suspicious that our furry pets exhibit such a graceful athleticism. Something else informed their scrutiny: “I don’t think this is real, there aren’t the right number of Olympic rings.”

The same week, many fell for a scuba diving dog, too, someone calling it “the luckiest dog in the world”.

Are we just soft for pets, or is our gullibility – that glitch in human design – the easiest button to push?

If you’re more into meerkats than cats, I made my own experimental animal diving competition video with Hailuo. Check out the Zoolympics!

TL;DR: Scuba-diving dogs. Cats doing Olympic backflips. Pope in a Balenciaga coat. Every new wave of AI-generated content exposes an old truth: people will believe just about anything if it looks real enough. But this gullibility isn’t new. From spirit photography to Photoshop, humanity has always stumbled through the early stages of new technologies. This article dives into our recurring trust in the unreal, unpacks the psychology behind digital belief, and asks: why do we keep falling for it, and what can we do about it?

Fake It Till You Monetize – Inside the AI Gold Rush

I’ve written before about how artificial intelligence is (ab)used to capitalize on our trust. From Glasgow‘s sour Willy’s Chocolate Experience to an entire AI art Facebook trend, the scam didn’t need to be sophisticated. Even in the early days of generative AI, when a subject could never have too many fingers, and buildings melted against the laws of physics, those images were still successful fraud traps for unskeptical observers.

Now, as text-to-video AI generators step up the game, distinguishing between AI BS and the real thing is becoming an even greater challenge for many.

All those “photographs” of adorable tiny homes and mountain logs of yesteryears have evolved into enticing moving images of “magical retreats”. You can now vividly imagine yourself stepping into this parallel universe where noiseless houses stand on “soft white sand beach”, hobbit homes “glow softly with lantern lights”, and your infinity pool spills into a Jurassic waterfall. All of it looks like something out of a dream, but many cannot call it.

Check it out – artificial visuals, artificial voice, real engagement!

Despite flooding different Facebook pages, these concrete AI videos all lead back to one shadowy source – Vacarino LLC. The owner of the website, which, nota bene, uses stock photographs, has a hidden identity. While Facebook pages seem to be based in Texas or California, and their AI properties are located in, well, Neverland, the linked website rents villas in – Italy. Under each property in Aosta Valley, Lazio, and Le Marche, reviews left by guests are obviously fake. They are even feverishly posted within minutes of each other. Everything screams red flag.

Last year, 404 Media discovered that Facebook/Meta has been paying people to generate viral AI images, offering up to $100 for every 1,000 likes through its Creator Bonus Program. Twitter/X‘s incentive scheme also turned out to stimulate AI slop, emotionally manipulative, algorithm-pleasing fluff that gamifies gullibility.

The earning potential of AI-generated videos, which often receive over 100,000 likes, is thus enormous.

With AI-generated videos now regularly collecting hundreds of thousands of likes, it’s easy to see why this ecosystem thrives. It doesn’t matter if the story features birds nesting in flowers during a storm, a civilian Father Christmas rescuing a whale family, or an Arctic wolf heroically saving a trapped penguin by bringing it to humans. If it looks kind, cute, or just shareable, it prints engagement.

And where there’s engagement, there’s money.

How many outfits do you need to change to rescue a penguin? Apparently, at least three.

Ctrl+Alt+Believe – Gen Z & Critical Thinking

You might assume that only your mom or grandma would fall for this stuff. But studies show that even Gen Z, the generation raised with smartphones practically welded to their hands, struggles to separate fact from fiction online. In fact, they might be the worst at it.

Born between 1997 and 2012, Gen Z is often praised for its digital fluency. But fluency isn’t the same as literacy. Being constantly online doesn’t make you any better at telling what’s real. According to research, digital natives are surprisingly prone to digital naivety.

Part of the problem? Critical thinking is rarely taught, especially not at the speed needed to keep up with fast-evolving technologies. Schools struggle to update syllabi quickly enough. So while students might know how to use ChatGPT to do their homework, they’re not necessarily taught how to question what shows up in those chats.

It’s tempting to look at the rise of AI-generated content and blame it on a shocking new ignorance – a sign of the modern mind’s decay. But the truth is less clickbaity and more human: we’ve always been like this.

Our tendency to trust, to be wowed by novelty, isn’t new. It’s hardwired.

History shows that every time a new technology emerges, humans go through a predictable honeymoon phase: a new tool appears → we lack the experience to understand it → blind belief ensues. From photography to radio to television to deepfakes, the pattern is reliable.

Want proof? Let’s take a look.

History of technological naivety

1. The Lie of the Lens – Early Photography

Before photography was invented in the 1820s, the closest thing to “capturing reality” was a painted portrait – expensive, time-consuming, and always at the mercy of the painter’s imagination. The level of detail and striking realism in early photographs was reminiscent of painted portraits, leading some people to struggle with distinguishing between the two media.

To many, the process seemed downright supernatural and unsettling. What kind of machine could trap a person’s image so perfectly? Some believed photography had the power to steal your soul. Others feared it could alter your very being, hesitating to get photographed. In the same way that some now worry AI will replace humans, 19th-century minds saw early cameras as something between dark magic and dangerous science.

Photography also struggled to be perceived as art, because it felt mechanical, detached, and thoughtless (as effortless as we could see pressing the “generate AI” button today).

Meanwhile, traditional artists of the time felt threatened by the new technology, fearing that once color photography got perfected, they would all be deemed useless and lose their jobs. Sound familiar?

Before the public had time to question how photographs were made, or how they could be manipulated and retouched, the camera quickly gained a reputation as a truth machine. If it were in a photo, it had to be real. That belief made fertile ground for fraud.

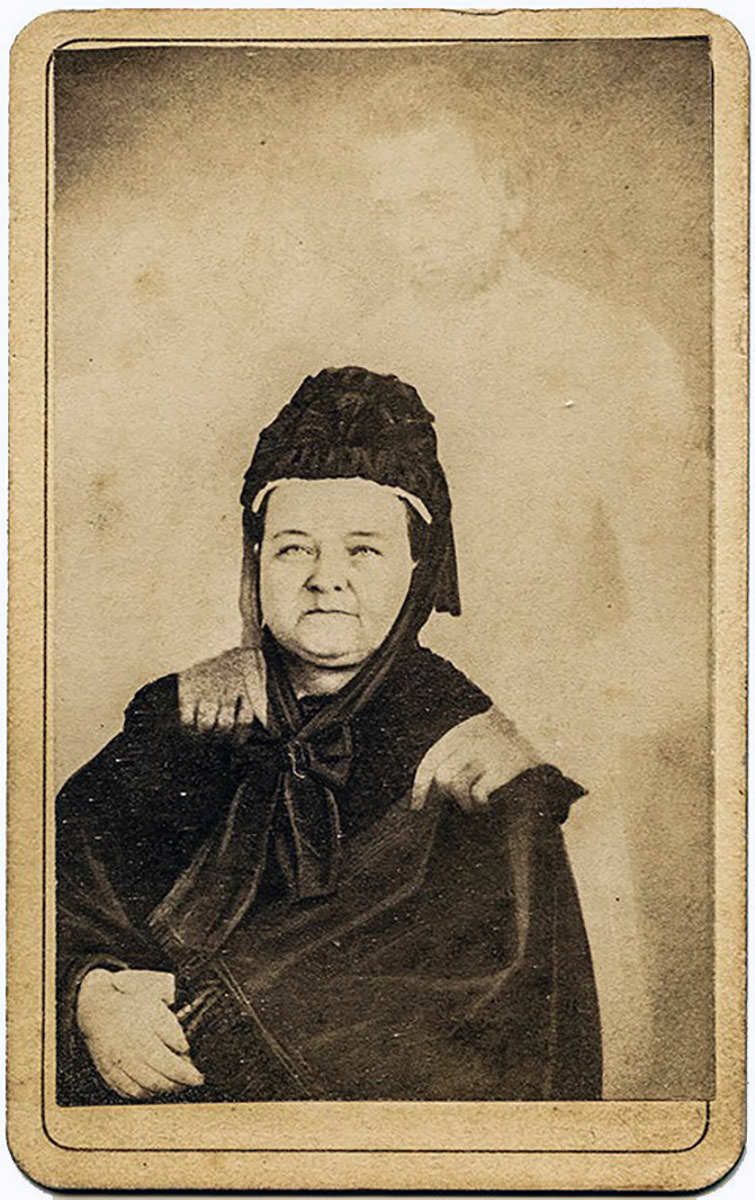

In the 1860s, William H. Mumler launched a booming business in “spirit photography” – portraits in which ghostly figures of the dead floated beside their grieving loved ones. Today, we know it was just a clever use of double exposure, but at the time, photography experts couldn’t crack the trick. The images were so emotionally powerful, so technically mysterious, that people suspended disbelief.

Paradoxically, P.T. Barnum, a showman legendary for his hoaxes, testified against Mumler in court, accusing him of profiting off grief. The prosecution, however, couldn’t prove beyond a doubt that spirit photography was a fabrication, so its inventor walked free.

The debates about Spiritualism were especially strong in the 1920s, with two unlikely opponents. Arthur Conan Doyle, a man of science and the father of the most famous detective Sherlock Holmes, was a true believer in spirit photography. The rational mind was coming from the world of trickery – magician Harry Houdini, a devoted skeptic, made it a personal mission to debunk fraudulent mediums.

2. Hello, Hell? – The Telephone’s Spooky Beginnings

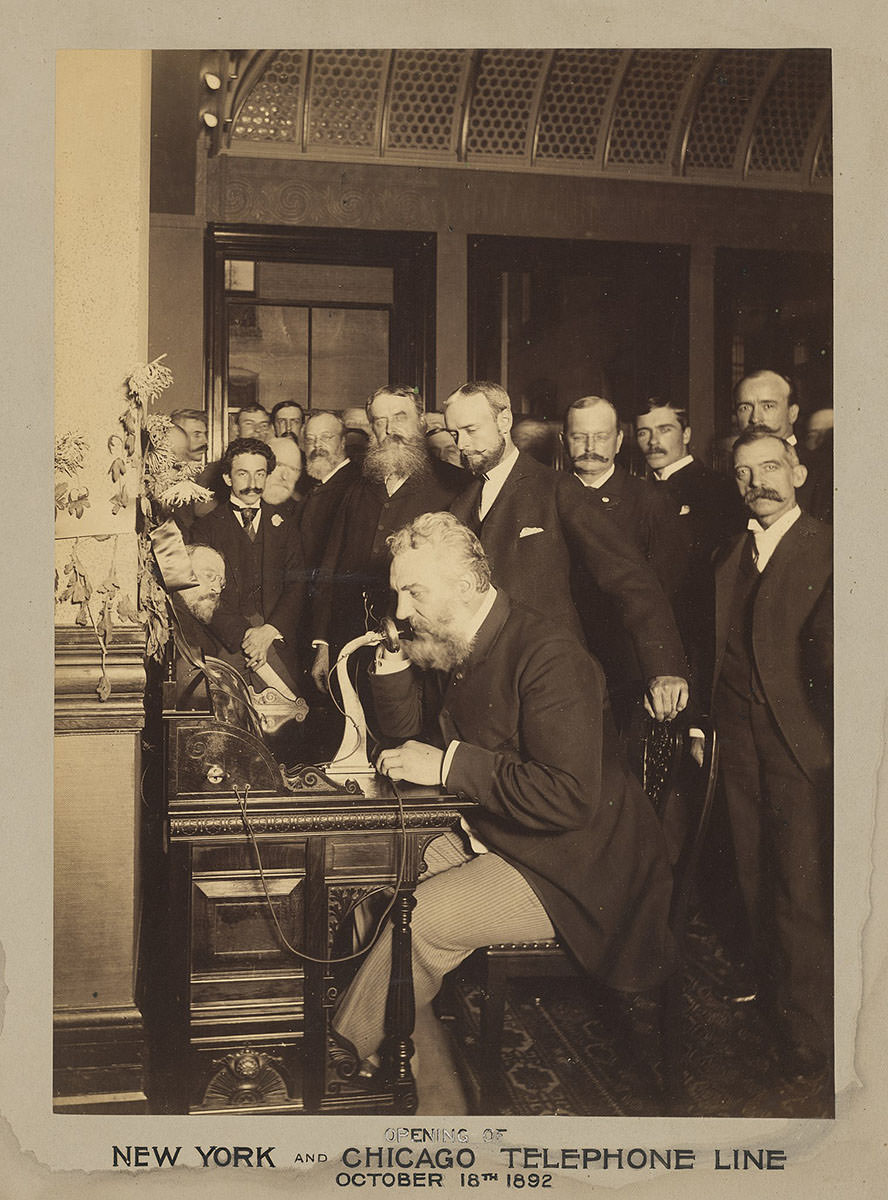

For centuries, long-distance communication meant waiting days or weeks for letters, or if you insisted on faster delivery, relying on smoke signals, flags, lights, and carrier pigeons. So when the telephone arrived in the 1870s, thanks to Alexander Graham Bell, the idea that someone’s actual voice could travel through wires and speak to you in real time felt, to many, like sorcery.

It was comparable to how spiritualists communicated with the dead. Suddenly, disembodied voices spoke from little boxes on the wall. Was it innovation, or necromancy? From the altars, priests spoke about the spooky telephone as a devil’s tool.

But the fears weren’t limited to the spiritual realm. Many believed the telephone was magnetic to thunder, that it could attract lightning strikes. Elderly people were afraid to touch the device, worried it might shock or electrocute them.

Some with chronic pain, however, took the opposite view: they believed those mysterious electric pulses might offer a cure for rheumatism.

Leaning on the booming pseudoscientific trend of electrotherapy at the time, one popular folk belief was that holding the receiver to an aching joint or sore body part could relieve pain or inflammation. Especially in rural areas, where medical access was limited, some believed the telephone could revitalize nerves or stimulate circulation.

3. Run for Your Lives! – Cinema’s First Jump Scare

When motion pictures were first shown to the public in the late 19th century, there were reports of audience members panicking because they believed that the projection was real and posed a threat to their safety.

Among the most notable examples is “The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station” by the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière. Even if the 1896 silent film depicting a train pulling into a station lasted only 50 seconds, it was incredibly lifelike for the early audiences.

See the train that managed to break the cinema’s fourth wall!

Confronted with moving images for the very first time, unlike anything they had seen before, the public had a strong emotional response.

Convinced a real train was about to burst through the screen and plow into them, the overwhelmed crowd screamed, ducked for cover, and even fled the theater in a stampede.

Today, the idea of running from a two-dimensional silent train might sound comical. But put yourself in their shoes: no special effects history, no cinema culture, no sense that a screen could show reality without being real.

The reaction wasn’t about stupidity. It was sensory overload, a shock to the system caused by a medium we now take for granted.

4. Martians Attack – The Night Radio Fooled America

In the early 20th century, radio was magic. A disembodied voice could suddenly fill your living room with music, news, or drama. It was miraculous, mysterious, and for many, unnerving.

Was it divine, or dangerous? Even religious leaders couldn’t agree. Some preachers called it a miracle for spreading the gospel; others saw it as Satan’s speaker system.

By the 1920s, when radio ownership exploded across the U.S., it became a kind of national campfire. But with it came a new problem: people didn’t yet have the tools to separate performance from reality, a fictional broadcast from a genuine news report.

Orson Welles‘ radio adaptation of H.G. Wells‘ “War of the Worlds”, which aired on October 30, 1938, was designed as a realistic portrayal of an alien invasion unfolding in real-time.

Listen to the broadcast that shook America!

Performed by his Mercury Theatre ensemble, Welles’ innovative format was presented as a series of fake news bulletins, complete with breathless on-the-ground reporters, scientific interruptions, and military briefings. To anyone tuning in late – or flipping channels away from the introduction – it sounded terrifyingly real: a Martian invasion in progress.

A mass hysteria spread among those who believed that the United States was under attack by extraterrestrials. The voice on the radio felt authoritative enough to override common sense.

Reports emerged of people hiding in cellars, fleeing their homes, grabbing guns for self-protection, or even dying of a heart attack. Newspapers at the time (bear in mind, they had a motif to discredit radio as a rising competitor for ad dollars) ran sensational headlines about car accidents, blocked highways, and suicides.

The extent of the panic was exaggerated, but it was an early example of fake news about fake news. Ironically, the real story might not be about mass panic attacks, but about how easily a new medium (radio) could be misunderstood, misrepresented, and mythologized, especially when the audience is untrained in skepticism.

5. As Seen on TV – Fiction Getting Real

Television, like every new medium before it, came with side effects. It didn’t just inform or entertain. It shaped perception, made the fictional feel factual, and occasionally inspired real-world action based on made-up plots.

When color TV was introduced in the mid-20th century, many viewers saw it as more than a technical upgrade. They believed color made things more real or accurate, compared to black-and-white.

When “Gilligan’s Island” (1964-1967), the American sitcom about a shipwrecked group stranded on a desert island, aired in color, concerned viewers sent telegrams to the U.S. Coast Guard, asking them to rescue the cast.

Check out if you would confuse the cast for castaways today!

In 1979, a fictional English heavy metal band Spinal Tap appeared in a parody sketch on ABC‘s “The T.V. Show”. Five years later, the group parodied a rock documentary, “This Is Spinal Tap”, which convinced many viewers that it was a real band. The film pioneered the mockumentary format, which audiences were unfamiliar with. Lacking a laugh track, people bought into fabricated interviews and concert footage. Despite the fictional history and discography, after the premiere, the actors released “new albums” and toured as Spinal Tap, once even opening for themselves as The Folksmen, another fictional band.

Watch the selection of the best Spinal Tap moments!

TV’s power to deceive wasn’t limited to the U.S. In the early 1990s, Croatia was swept up in the American soap “Santa Barbara”. While the show didn’t find massive success back home, in post-Yugoslav households, it was a sensation. So much so that when Eden Capwell, a central character played by Marcy Walker, ended up in a wheelchair after a dramatic accident, an elderly woman in the town of Sinj donated money to the local church. The reason? She wanted a Mass said in Eden’s name, praying for her recovery.

Watch when Eden surprises Cruz with “something she was praying for”!

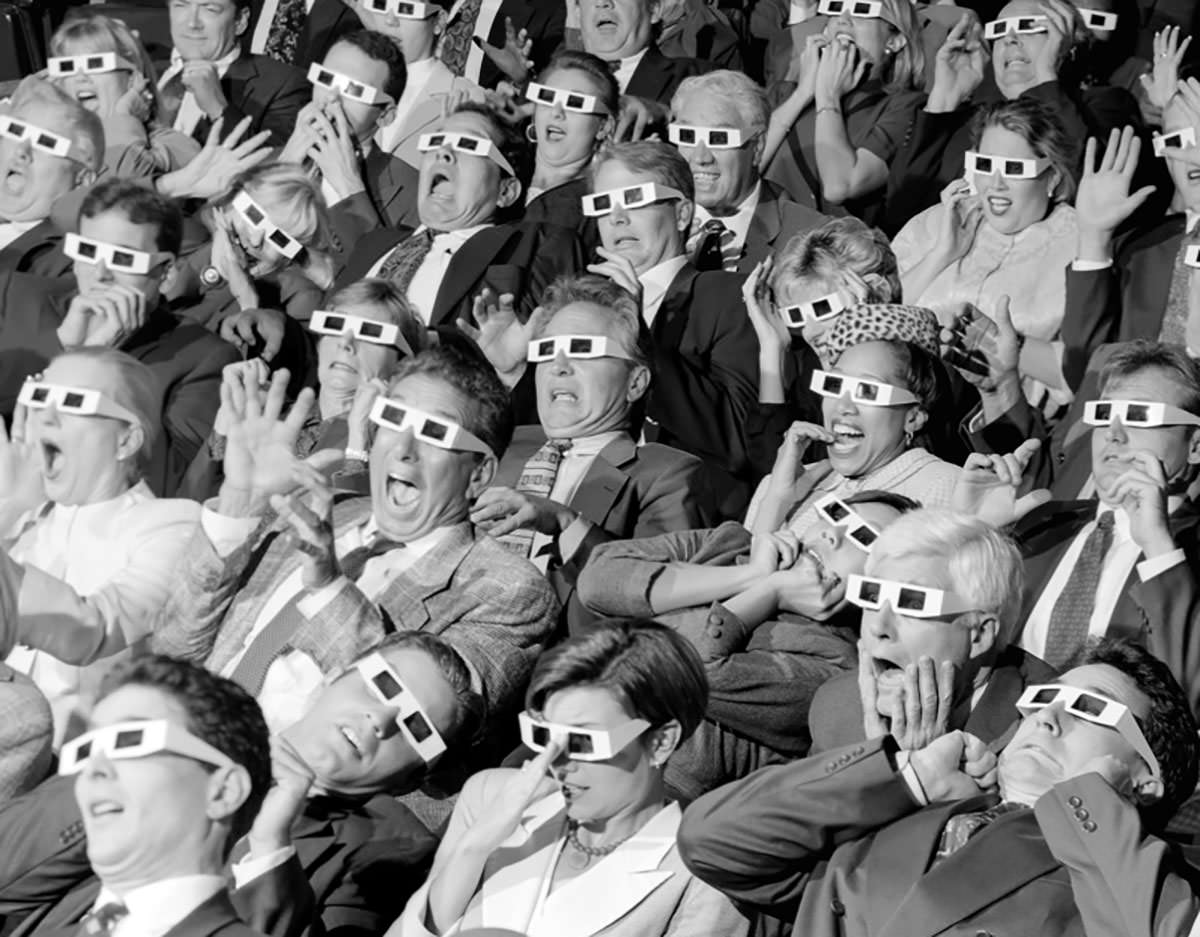

6. Coming Right At You – The 3D Illusion

Competing with the successful TV market, Hollywood introduced the new gimmick – 3D cinema.

The three-dimensional movies exploded in the 1950s, and audiences once again forgot they were watching fiction. Viewers ducked to avoid on-screen spears, shrieked when objects seemed to leap from the frame, and left theaters feeling as if they had been somewhere else.

Decades later, James Cameron’s “Avatar” took immersion to new heights, so much so that some viewers experienced “Post-Avatar Depression”, mourning the fact that Pandora wasn’t real.

Whether it was old-school red-and-blue glasses or modern polarized 3D, the effect was the same: depth created belief.

Today, AI-generated videos use similar tricks (dynamic camera movement, shallow depth of field, lighting effects) to simulate realism and override our critical faculties. Make it move, and people will believe it.

See the trailer for the movie that got its own syndrome!

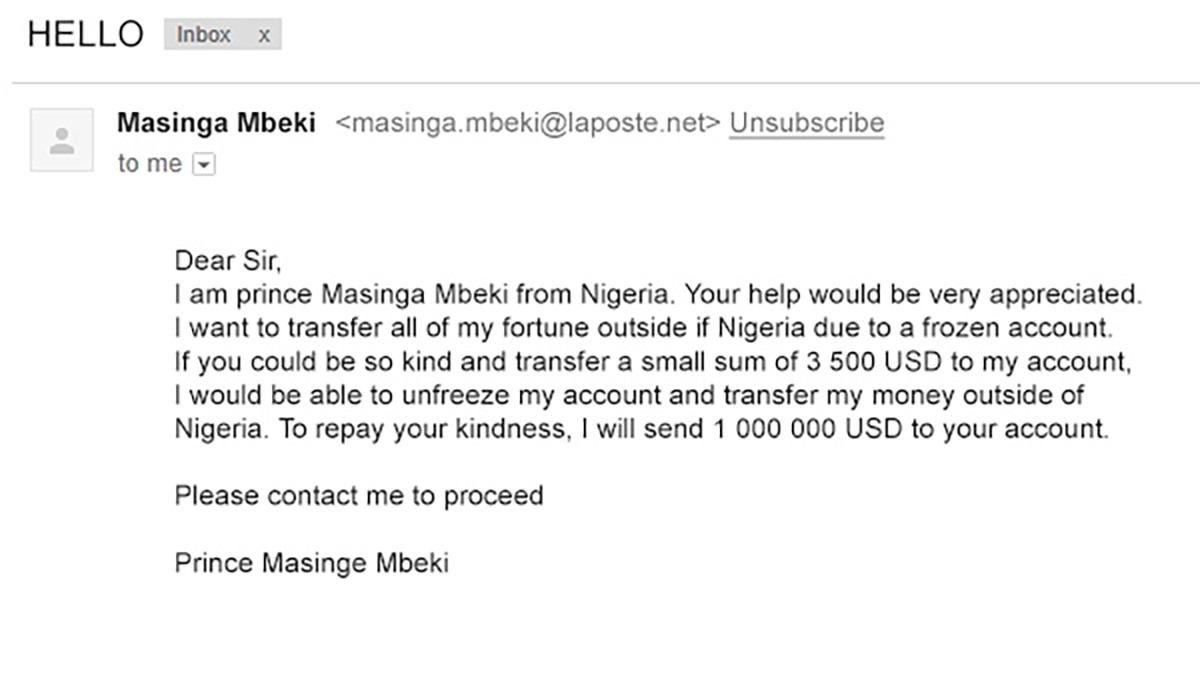

7. You’ve Got Mail – it’s Nigerian Prince

When the internet first entered people’s homes in the late 1990s and early 2000s, it arrived with a cheerful dial-up tone, a blinking cursor full of promise, and absolutely no sense of danger.

Back then, most excited users approached the web like a digital utopia: a place of free information, instant communication, and infinite curiosity. And into that wide-eyed optimism flooded a tsunami of scams, hoaxes, and copy-paste curses.

Perhaps the most innocent and persistent of these were the chain emails. They warned that if you didn’t forward a message to 10 friends, you’d be cursed with seven years of bad luck. Some were spiritual (“An angel will visit you tonight!”), others menacing (“Delete this and DIE”). But what they all exploited was the same thing AI-generated videos do today: a shortcut past your critical thinking, straight to your fear or hope.

Then came the scams. The most notorious? The 419 email, aka the Nigerian prince fraud. “Dearest Friend”, it would begin, in a suspiciously flowery tone. “I am a prince in need of help transferring $50 million…” The grammar was poor. The story made no sense. But thousands, even millions, clicked, replied, and wired away savings. The medium felt trustworthy. After all, it arrived in your inbox, addressed personally. How could it be fake?

The early web was a scammer’s playground and an honest user’s booby trap. Phishing links disguised as promotions, virus-ridden .exe files downloaded with a single click, and pop-ups declaring “YOU’VE WON!” while quietly hijacking your browser – all succeeded not because people were stupid, but because they were naive. The rules weren’t clear yet. We believed what we saw. We clicked before we thought.

And we still do it, on social media, clicking on links as soon as our friends drop a DM with a “request for help”.

Remember those legal-sounding Facebook statuses declaring “I do not give Facebook permission to use my photos”? Or the annual panic post about a new privacy policy, which users believed could be invalidated by copy-pasting a bold paragraph into their timeline? That’s not how contracts work. But millions shared those statuses, only self-identifying as susceptible fraud targets.

We’ve moved from “forward this to avoid a curse” to “watch this dolphin rescue a baby zebra from a tsunami”. But the formula hasn’t changed.

Check out how thousands of people lost money thinking they participated in lost luggage sales advertised on Facebook!

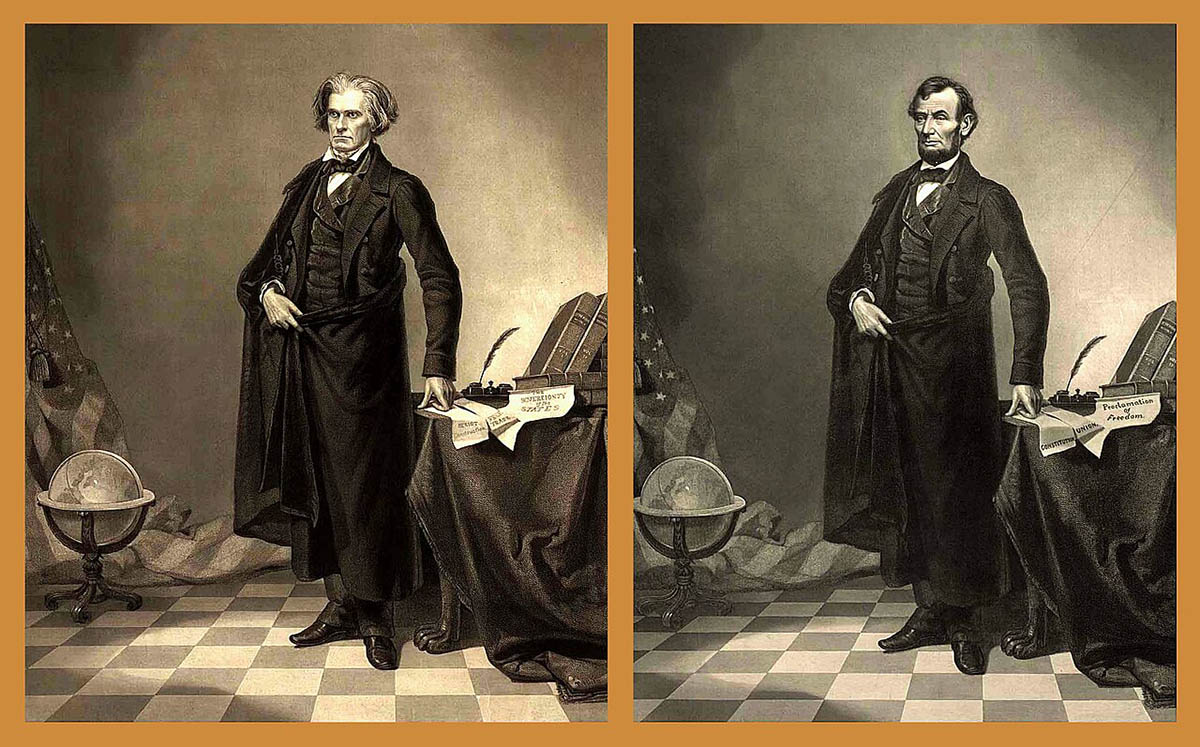

8. The New Era of Digital Deception – From Photoshop to Deepfakes

Photoshop arrived in the late 1980s, but the public had already lived through manipulated photographs – from Abraham Lincoln‘s head placed on John Calhoun’s body for the President’s most iconic portrait to Stalin airbrushing rivals out of existence.

Photoshop democratized deception. Suddenly, anyone with a mouse and patience could edit reality, and make it beautiful, dangerous, or just fake.

With manipulation getting more subtle and results more polished, audiences started trusting the perfect over the possible. For instance, retouching of models’ appearances in fashion journals stimulated a whole range of eating disorders among teenagers, who believed the deception.

Remember the viral photo of a shark leaping toward a helicopter? Or the widely circulated image of “Mars Spectacular” supposedly appearing as large as the Moon on August 27? Both were fake – Photoshop creations passed around as scientific marvels or National Geographic-style moments. Yet millions believed.

Then came deepfakes, and things got weird. In 2017, a Reddit user released a video showing celebrities’ faces swapped into porn. Not just a static edit, but a moving, blinking, speaking face, artificially generated, frighteningly realistic. Within months, Barack Obama was delivering words he never said. Then we got Tom Cruise doing TikTok magic tricks. Donald Trump got arrested. Pope Francis rocked a Balenciaga puffer coat.

Watch coin magic performed by one and NOT only Tom Cruise!

@deeptomcruise I love magic!

Unlike Photoshop, which was still rooted in manual skill, deepfakes were powered by AI, and they were getting better by the week. Audio could be cloned. Mouths could be synced. Entire videos could be fabricated from scratch, in minutes.

And it resulted in an accidental belief. People shared, liked, reposted, laughed, and panicked. Not because they were foolish, but because we’re all conditioned to believe what we see, especially when it moves.

Psychology of believing fake content

If all this sounds like a parade of facepalms, it’s worth pausing to remember: falling for fakes isn’t stupidity. It’s psychology.

Humans are wired to trust what they see and hear, especially when it mimics the physical world. This makes evolutionary sense. For most of human history, our eyes and ears were reliable sensors. If you saw a tiger, it was a tiger. If you heard thunder, a storm was coming.

But modern media exploits these same instincts with manufactured visuals, hyperreal audio, and emotionally loaded narratives that hijack our attention and bypass critical filters.

Psychologists have identified several key reasons we keep falling for fabricated content:

Cognitive ease: If something is fluently presented (clear, high-res, emotionally engaging), our brains are more likely to accept it as true.

Confirmation bias: We believe what aligns with our existing beliefs or hopes, whether it’s a diving dog or a politician’s “leaked tape”.

Emotional hijacking: Viral content often evokes outrage, awe, cuteness, or fear, all of which impair critical thinking and boost shareability.

Authority by aesthetics: If a video looks professionally produced, we’re more likely to trust it, regardless of its source.

Social proof: If thousands of others are liking, sharing, or commenting with wonder or tears, we’re more likely to join in than question. Virality reinforces belief, belief produces virality – it’s a loop!

And when the pace of technological change outstrips our capacity to adapt, we’re left running on instincts evolved for the savannah, not synthetic images of cats doing Olympic backflips.

Why We Fall for AI-Generated Videos – Conclusion

We’ve come a long way from fleeing Lumière’s oncoming train or forwarding chain emails to avoid seven years of bad luck. And yet, every time a new technology emerges (photography, radio, Photoshop, AI), humanity briefly forgets how to think. We reset the learning curve. We marvel, share, and fall for it. History repeats itself.

That’s not a failure of intelligence. It’s a side effect of being human, a recurring glitch in our collective operating system.

Today it’s Cat Olympics and dogs in scuba gear. Tomorrow, it might be political speeches and fake eyewitness footage

Our minds are meaning-making machines. We crave stories, we trust our senses, and we lean on emotional cues to navigate a chaotic world. But in the age of AI, our senses can be fooled faster than we can fact-check, and emotion can be engineered with terrifying ease.

Today it’s Cat Olympics and dogs in scuba gear. Tomorrow, it might be political speeches, fake eyewitness footage, or loved ones’ voices asking us to wire them some money.

Every generation has had its “this technology is going to ruin us” moment, and much of it echoes the same underlying anxieties: loss of control, blurred boundaries, and machines meddling in roles once seen as sacred.

We don’t need to become cynical robots. But we do need to learn how to pause before we believe, and doubt before we share.

Until we can say: a critical thinker is born every minute.

Did you ever fall for AI-generated videos?

Share your comments below, and pin this article for later!