The Eurovision Song Contest was founded in 1956, partly to unite a post-war Europe. In 1991, 35 years after the first notes were sung in Lugano, the Soviet Union was dissolved, and the Cold War ended. Now, another 35 years have passed since the fall of the Iron Curtain, and the European Broadcasting Union decided to celebrate Eurovision’s 70th birthday by launching the very first Eurovision Song Contest Live Tour, with a quietly erected brand-new barrier. Let’s call it the Irony Curtain. Still powered by that unfortunate slogan “United by Music”, the summer concert series, quite remarkably, unites Europe by visiting only one part of it: Western Europe.

Is Eurovision Song Contest Live Tour a clever celebration, or the latest fiasco of a project losing its compass?

Yes, the forgetful 70-year-old granny is going on the road, bringing together ten artists from Eurovision 2026 alongside selected “iconic acts” from the competition’s past. Nemo, the 2024 winner who famously returned their trophy in protest of Israel’s participation in Eurovision, will not be there. Neither will Conchita Wurst, Eurovision’s 2014 champion, who publicly withdrew from all Eurovision-related activities just days ago.

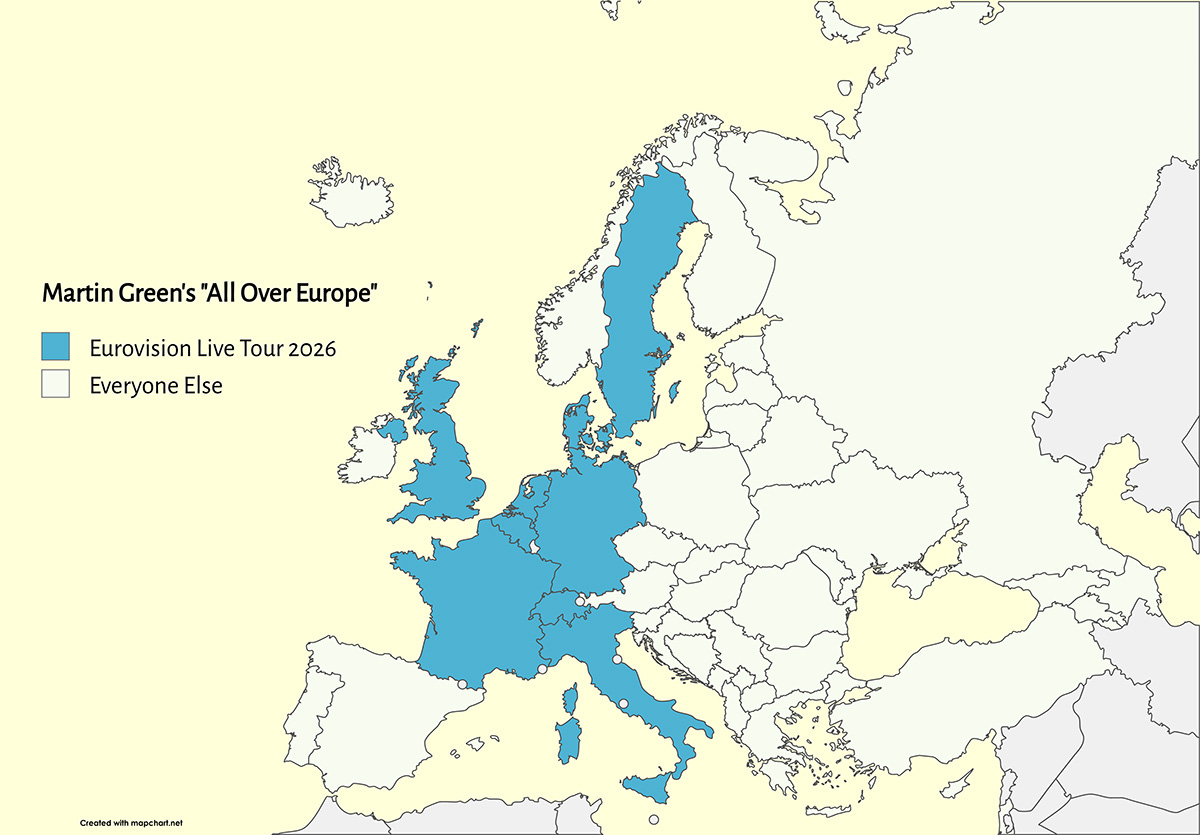

The special arena events with an unknown lineup will grace ten privileged locations in June and July: London (UK), Hamburg (Germany), Milan (Italy), Zürich (Switzerland), Antwerp (Belgium), Cologne (Germany), Copenhagen (Denmark), Amsterdam (Netherlands), Paris (France), and Stockholm (Sweden).

“For the very first time, we are bringing the magic of the Eurovision Song Contest live experience directly to fans and their friends and families all over Europe”, declared Martin Green, Eurovision’s Director, with a straight face. He did not clarify how “all over Europe” came to mean a comfortably compact triangle between London, Milan, and Stockholm.

This tour not only overlooks vast swaths of the continent – especially Central and Eastern Europe – but arrives precisely when multiple countries have stepped away from Eurovision itself, protesting the EBU’s political decisions.

Is Eurovision Song Contest Live Tour, pitched as a jubilant tribute to Eurovision’s seven decades, a clever celebration, or the latest fiasco of a project now literally losing its compass?

Why is Israel in Eurovision, you ask? Check it out.

Concentration (in) Camp

Eurovision affirmed its position as a hostage of Israel, convinced that wrapping the contest’s unprecedented wounds in a bandage made of sequins might somehow bring the patient’s fever down. With such a spectacular misdiagnosis, one that has already resulted in participation dropping to 35 countries (the lowest number since the introduction of the semi-finals in 2004), it feels almost surreal that the EBU would come up with a project that further tightens its circle, severing already loosened ties with what is left of Europe in its deserted trenches.

The Eurovision Song Contest Live Tour effectively concentrates all its sound systems into nine (mutually bordering) countries of the continent’s west.

Indeed, nine, because Germany appears twice, with both Hamburg and Cologne proudly qualifying as two of the EBU’s “10 major European cities”.

The two more A-listers, Antwerp and Amsterdam, are so major that even their mere 160-kilometer distance did nothing to exclude either. A Eurostar train passenger can travel between them in roughly 75 minutes, while the car’s most fuel-efficient route demands just over 100 minutes. Still, both Dutch and Belgian cities get their very own Eurovision night.

In comparison, a Eurofan from Lisbon would have to drive 18 hours to the nearest concert in Paris, one from Athens could easily make it to Milan in less than 23 hours, while an Azerbaijani concertgoer from Baku could truly prove their devotion by spending 50 hours behind the wheel to reach Zurich, a modest 4,200 kilometers away.

Instead of truly giving “those who can’t attend the shows in Vienna the chance to share the magic of Eurovision”, the ESC Live Tour designed in EBU’s headquarters serves only the comfort of the selected strip of Europe east of the UK and west of Italy.

Why does only one third of the room (coincidentally, the richest third) get to dance?

Not all of Eurovision's live concerts go according to plan. Learn how subliminal jihad messages invaded the performance of Baby Lasagna!

€-vision’s Iron Curtain

The EBU’s celebratory Live Tour sidesteps the contest’s most explosive controversies. Except for the Netherlands, the ISIS countries (Ireland, Spain, Iceland, and Slovenia), which have all boycotted the contest following the EBU’s decision to allow Israel to compete in Austria, don’t appear on the tour itinerary.

Spain (a former member of the Big Five) and Ireland (a country with a record-equalling seven victories) are both major Eurovision players, but seemingly too hot potatoes for the EBU to handle at the moment.

Should we read the Eurovision Live Tour as a way to compensate for the financial losses caused by the withdrawal of former key contributors?

All selected cities sit within high-GDP, advanced economies. In fact, the tour stops are located in nine of the top 15 richest European countries. They are a sharp cut of the continent’s economic core, not just big in absolute GDP figures, but also on a per-person basis.

In reality, these fans can afford to travel the farthest. Yet, they simply won’t have to, as fans from poorer, excluded regions are expected to hop on planes and absorb the extra costs.

Rings like the legendary “Let them eat cake”. And we know how Marie Antoinette ended.

Eurovision Song Contest Live Tour makes no stops in Central or Eastern Europe – even though nations like, for instance, Poland, Greece, and those from the territory of the former Yugoslavia (competing since 1961) have vibrant Eurovision followings and strong fan cultures. From the Baltics to the Balkans, Eurovision’s Iron Curtain descends. All the bets are on the West.

Why this pattern? One plausible interpretation is economic:

Arena sizes and ticket revenue: Western European cities like London (O2 Arena) or Paris (Accor Arena) offer massive venues where organizers can sell tens of thousands of tickets and premium hospitality packages.

Tourism infrastructure and disposable income: Western capitals benefit from constant tourism flows and more affluent concertgoers likely to buy tickets to multi-hundred-euro packages.

In other words: is this really a cultural tour celebrating Europe, or a profit-centered “€-Vision Live Experience” engineered to extract maximum revenue from the wealthiest markets? The absence of major Eurovision markets in Central and Eastern Europe raises this question sharply.

A Happy Narrative in a Polarized Moment

In its official announcement, the EBU frames the Eurovision Song Contest Live Tour as a joyful tribute to Eurovision’s “legacy, its global fan community, and seven decades of unforgettable music”.

A harmless celebration, at least on paper.

In reality, that messaging collides with two inconvenient truths.

a) Dancing Around Political Conflicts

The wave of boycotts is rooted in serious humanitarian and political concerns. Yet the Live Tour is being marketed as pure spectacle.

The staged narrative of “70 magical years of Eurovision” stands in stark contrast to the lived experience of many fans who feel the contest has lost its apolitical sheen and now represents Europe’s broader political fault lines.

Since 2024, the Israel controversy has overshadowed every edition of Eurovision, and the Live Tour is being positioned as conveniently insulated from that reality.

Rather than engaging with difficult debates about neutrality, broadcaster responsibility, and cultural ethics, the EBU redirects attention toward arenas, ticket sales, and feel-good branding.

Eurovision, repackaged as a rock-show-style touring product, becomes easier to sell – and easier to defend – than Eurovision as a contested cultural institution. In the context of the controversies rooted in ethical division, this megaphone moment could be perceived as a commercial diversion, designed to amplify nostalgia while muting uncomfortable questions.

b) Economic Priorities Over Inclusive Representation

By concentrating exclusively on Western Europe’s largest and wealthiest stadium markets, the Live Tour sidesteps major parts of the Eurovision world that are politically vocal, culturally engaged, and critically invested in the contest’s future direction, especially in Central and Eastern Europe and in boycotting nations.

If Eurovision’s mission were genuinely about unity, one might expect a tour that visits a symbolic cross-section of Europe – including cities such as Belgrade, Warsaw, Tallinn, Bucharest, or Sofia – not just affluent, Western capitals. Instead, the map stops where purchasing power drops.

The Eurovision Live Tour is a model that mirrors standard corporate entertainment logic: choose wealthy markets first, fill the biggest arenas, sell premium experiences, and leave the rest (including hard conversations) off the road.

Eurovision Song Contest Live Tour – Conclusion

In the wake of political boycotts, public broadcaster walkouts, and mounting demands for transparency, Eurovision’s Live Tour feels less like a unifying cultural odyssey and more like a commercial rollout designed to:

- Celebrate in markets least disrupted by controversy

- Capitalize on reliably lucrative audiences

- Generate revenue at a safe distance from the political costs borne by countries that chose conscience over competition

Making Stockholm its easternmost destination, Eurovision’s Live Tour doesn’t just show geographic ignorance, but institutional arrogance

The Eurovision Live Tour may indeed offer fans joyous evenings of spectacle and sing-alongs, and there’s value in that.

But as political polarization increasingly intrudes upon what is still marketed as a cultural event, it is hard not to see this tour as at least partly an institutional maneuver aimed at redirecting attention and energy away from deep tensions and toward familiar pop-cultural enjoyment.

In trying to steer the gaze away from Israel, the “United by Music” contest has managed to divide Europe once more, now with a clear, Irony Curtain line.

Because, when the Live Tour promises to “travel across Europe this summer”, and crowns Stockholm as its easternmost destination, the result is not the sign of merely geographic ignorance – but also institutional arrogance.

With so much money invested each year in ever more dazzling light shows, it is a striking and unforgivable flop that Eurovision’s Live Tour spotlight has left two-thirds of the continent in complete darkness.

Do you plan to attend the Eurovision Song Contest Live Tour?

What’s your take on it?

Pin the article for later!