In southern Switzerland, just where the French-speaking part of the Canton of Valais becomes the German-speaking Wallis, the town of Leuk holds a secret. That secret has nothing to do with the fact that the Onyx spy system has been installed on its territory. Even more arcane than intercepting communication between the living targets, the cryptic vibe spreads in the literal underworld of Leuk, among the dead. In the obscure basement of the Church of St. Stephan, 22,000 neatly displayed skulls form a wall of silence. Beinhaus Leuk is a charnel house with some tight-lipped householders hiding under the prayers’ feet for centuries.

For every breathing inhabitant of this Swiss town, there are five skulls in Leuk Charnel House

Better known for the rejuvenating thermal baths of Leukerbad, a resort village higher in the Alps, it seems Leuk Stadt has a rather chilling core. The grand collection of skulls and bones under the parish church was practically the backbone of the town’s religion since medieval times. Today, 4,000 souls are living here (85% of them Roman Catholic) and, for every breathing inhabitant, there are five skulls in the Ossuary of Leuk.

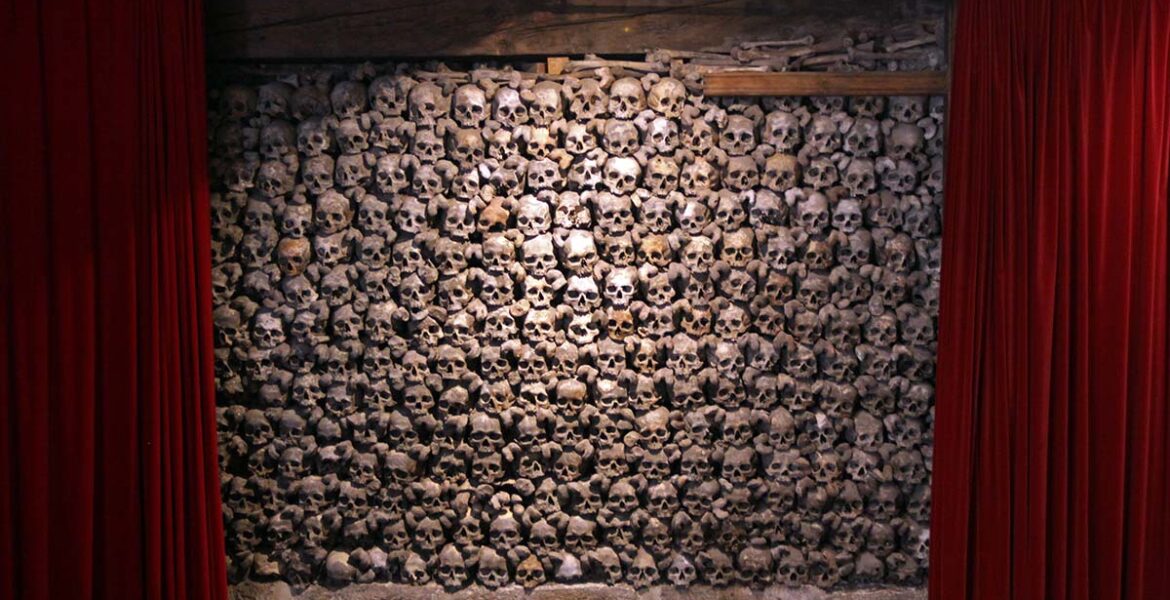

As I stepped into this room where bricks have been replaced with bones, the setting with red curtains transported me to David Lynch‘s atmospheric waiting room, revoking the ultimate mystery of my childhood: who killed Laura Palmer? In “Twin Peaks”, spirits inhabit the space behind the curtains of the Red Room in Dale Cooper‘s dream. It is here that The Man from Another Place tells FBI’s special agent, in a creepily distorted voice: “She’s filled with secrets.”

Skulls in Leuk’s ossuary talk less than Laura Palmer. In fact, they’re missing their jaws. With such silent witnesses, it is not easy to dig into the Leuk Charnel House history. But today, we’re gonna peek inside, behind the skull wall and its meaning. Join us on the Beinhaus Leuk tour!

From flying witches to papal hair

Rising on the hills of Leuk, an imposing tower overlooks the Rhone Valley. While the belfry is Romanesque in style, the rest of St. Stephan’s Church is – Gothic. It all grew above the walls of the 2nd-century fireplace, presumably a Roman rest stop, with the first religious building appearing in the 6th century. Today’s cathedral, completed in 1514, stands on the site of six church complexes constructed successively in the Middle Ages.

Ulrich Ruffiner, the architect who finished the task, was not even born when the grand reconstruction started in the late 1470s. But the young master builder quickly gained the trust of Cardinal Matthäus Schiner and the town of Leuk, which would later authorize him for another job – transforming the residence of the Sion bishop’s representative into the Leuk Town Hall in 1541.

Even today, the rulings of the district court in this Rathaus are “supervised” by a crucified Jesus on the wooden wall. Not the greatest reminder that just a century before the burnt building’s reconstruction, the local wood was used in another ultimate justice project: the infamous Valais witch trials. The eight-year hunt that started in 1428 was the first European system to purge the society of Devil’s associates who could fly, become invisible, or turn into werewolves. All it took to end one’s life in flames was having three neighbors stating the accusation.

The main entrance to St. Stephan’s Church was closed when I visited. On the notice board, there was no mention of Leuk Bone House. Just opening hours of the parish office (once a week), a schedule of Bible readings and masses, complete with a list of parishioners who paid for them, an introduction of the new vicar from India, and an invitation to the police pastor’s presentation.

There was also one rather unusual announcement that testifies how religious can an obsession with material objects become. That’s especially surprising when it’s practiced by the same organization that would’ve labeled similar “magic rituals” as witchcraft.

On the 13th of August 2023, the Archbishop of Lviv Mieczyslaw Mokrzycki, who served as a personal secretary of Pope John Paul II, gifted a piece of his former boss to the church. The relic capsule contained the pope’s hair, with a certification decree declaring: “May the people of God pray before this relic. They may, through the intercession of St. John Paul II, receive graces. May they imitate him in faith and zeal.”

If you're a fan of unusual relics, you'll want to learn the story of St. Valentine's skull in Rome!

St. Stephan’s secrets

The northern side entrance to St. Stephan’s Church was unlocked, and I stepped inside. It was just me and silence in the grand space seemingly filled to the brim with objects considered precious. It was not immediately obvious where they kept them, but the bilingual warning in an oversized font was trying to ward off the potential wrongdoers: surveillance is constant!

There was a usual set of altars, religious sculptures, and a pulpit so intricately carved that even the wood must’ve been saying its prayers. The church named after the first Christian martyr was telling a usual story. Christ was the enthroned judge, surrounded by Mary, apostles, and angels. The trumpets were calling the dead from their graves. The good were on their way to heaven, while the jaws of hell would devour the wicked.

In the southwestern corner of the church, a 1378 bell stood on display, with no worries that anyone could steal it. It’s not a piece of hair, after all. In Latin, the inscription declared: “I praise the true God, call the people, gather the clergy, mourn the dead, drive away the plague, brighten up the festivals.”

The opposite corner revealed some of the statues excavated from the piles of bones in Beinhaus Leuk, which I was still on the hunt to find. The church wall hosted a crucifix of exalted Jesus dating back to the third quarter of the 14th century. Right beside it, stood an early 14th century Pietà. It’s not just considered one of Switzerland’s most valuable statues; it has a European significance too.

Next to the 17th-century Meschler Altar in the side aisle, a set of stairs led down into the crypt. Behind the alarm-protected bars, there were more sculptural depictions of God the Father, the Mother of God, St. Sebastian the martyr, and other saints.

The thousands of skulls were still far from my sight, but one exhibit stole all my attention – a human corpse.

Leuk Mummy

In 1981-1982, St. Stephan’s Church went through yet another renovation, with plans to install a new central heating system. The excavations under the floorboards of the church found several skeletal remains. This was not so surprising as burying people inside the sacral objects was a common practice in medieval Switzerland. The dug-out human remains were reburied in the cemetery.

But in the southern aisle, close to the position of that multitasking bell bragging to equally brighten up the festivals and mourn the dead, the workers stumbled upon a wooden coffin with something special inside. Grave No. 58 was hiding a well-preserved mummy. She lay there, her fingers interlocked in a praying position on the chest.

The mysterious body that was never embalmed belonged to a nameless slender woman, probably in her fifties. The researchers called her The Woman from Leuk. The open-sided latchet shoes revealed she was buried in the 1630s, and her garments – a brownish-red ankle-length skirt paired with a white short blouse – corresponded to the Spanish fashion of the time.

While her small stature (151 cm in height) and gaping mouth with two remaining teeth screamed with questions, the mummy of Leuk was not so unique. Renovations in Swiss churches have a way of discovering bodies that refuse to decompose. Such was the case with Baron Johann Philipp in Senwald Church or Anna Catharina Bischoff in Basel‘s Barfüsser Church.

Likewise, the mummification magic in Leuk was linked to special local conditions, such as a dry climate and a humidity-protected terrace on which the church was erected.

“The fact that the individual was buried in the southwestern corner of the church in an older masonry grave attests to a certain status of the woman within the society”, the scientists wrote. “It was a privilege and sign of social distinction to be buried within the church rather than outside in the cemetery, with the most coveted places close to the altar or in the choir.”

Cloaked in a simple cape, with folded hands the conservators moved to the pelvis area, Leuk’s mummy is now displayed behind the trellised gate of St. Stephan’s Church crypt. The original casket is now covered with a glass case.

Discovery of the Leuk Ossuary

While I was trying to open every locked door in the vicinity of the crypt, I just couldn’t find the entrance to the Leuk Ossuary in this eerily quiet church. I knew it had to be in the basement, but after circling the nave, and completing my very own Way of the Cross, I practically gave up on hopes of finding the cellar of bones.

I exited St. Stephan’s Church, circled it, and suddenly found myself in a charming rose garden. On the southern side of the church, just next to a crucifix with life-sized Jesus, stood a simple wooden arched door. A little plaque was warning visitors about video surveillance. That had to be it.

Danse Macabre from medieval times: the 22,000 skulls at Beinhaus Leuk, a bone house that has been hiding in southern Switzerland for over a century. The 20-meter-long wall made of human craniums is more than 1.5 meters deep! #leuk #switzerland #bones #skulls #church pic.twitter.com/nfS2SwHnDW

— Pipeaway (@pipeaway_travel) October 29, 2023

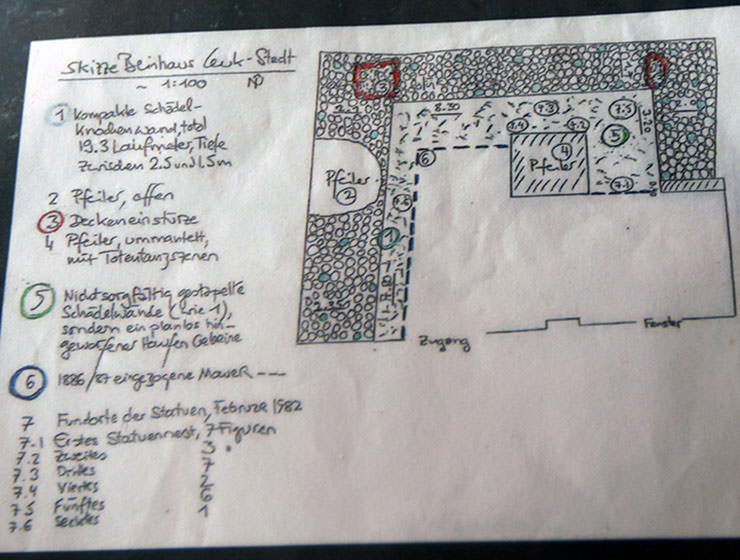

Discovering the entire scope of the Leuk Ossuary four decades ago wasn’t as straightforward as just knocking on anything that looked like a door. The 1981 church renovation uncovered the original floor of the central nave, and surprisingly – found larch planks that shouldn’t have been there. Those were the beams forming the ceiling of the chamber underneath! The excavators headed down to the small ossuary chapel under the southern aisle, removed a cupboard, and broke through the thin northern wall behind it. The underworld of skulls was staring back at them.

The church council had considered the idea of expanding the chapel into a community center. For the needs of the living, the dead had to go out. They dug out the pit in the churchyard and filled it up with skeletal remains. Those beautiful blooming roses grow above a mass grave!

In February of 1982, a team of archeologists led by Georges Descoeudres and Jachen Sarott tunneled through the bones and found further discoveries nested inside. Gothic and Baroque religious statues and crucifixes, 26 in total, were sharing the final resting space with the skulls of Leuk Beinhaus. From scroll-bearing angel and knight statues to pietas and saints such as St. Magdalene, St. Sebastian, St. Michael, St. Barbara, St. Bartholomew, and St. Maurice, the collection was remarkable. Of course, there was no shortage of representations of Jesus Christ either.

The plan of building the club for the community had to be deserted. The ossuary was far larger than anyone had expected, so when they reached the current layout of the skull wall, they stopped digging. There’s still speculation that even older precious artworks from the Romanesque period might lie inside the church’s skeletal foundations.

For even more churches made of bones, head to the other side of the border. These are the most fascinating ossuaries of northern Italy!

Inside the Leuk Charnel House – painful Jesus and skull choir

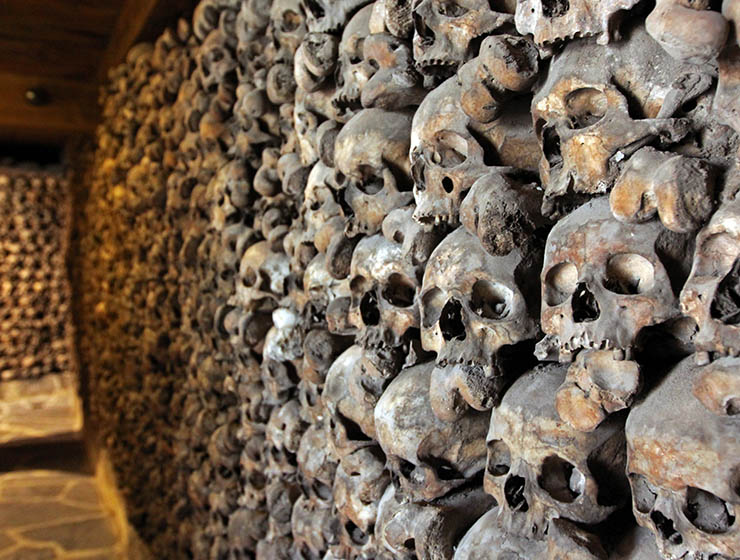

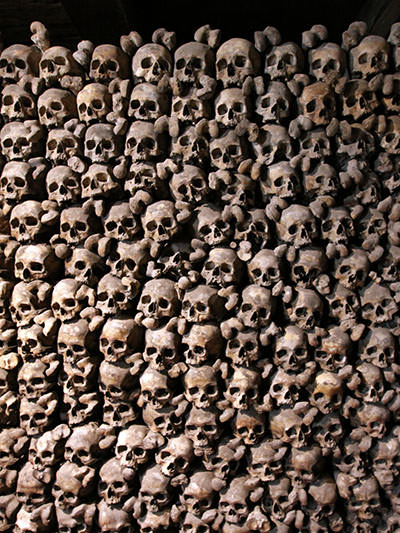

Entering the Beinhaus of Leuk is like getting into a room full of people who suddenly fall silent – the eeriest surprise party. Closing the wooden door leaves the sound of the street behind, and immediately faces you with some self-reflection. Thousands of eye sockets seem fixed on you, an unblinking audience.

Between the stone floor and the wooden ceiling, the skull wall angles twice. In total, it covers 19.3 meters in length and reaches 2.4 meters in height. These skulls belonged to 22,000 individuals (maybe even more, depending on who’s doing the math). Only later I would find out that what I was seeing was just a tip of the skullberg.

Heidi, a guide who leads free summer tours of Leuk Stadt, talked to me in Swiss German. Now, that sounds like a linguistic riddle made for the Onyx system itself, but I managed to decipher; in Leuk Ossuary, there’s more than meets the eye. Behind the visible facade, the skull walls go deep, extending between 1.5 and 2.5 meters!

“There are smaller bones inside”, she shed light on the unseen layers of Leuk Charnel House. “Then again comes a wall of skulls and thigh bones.”

Meticulously arranged and balancing on each other, the skulls have a guardian in the front row, Heidi called him – a painful Jesus. The Son of God is crucified in the bloodiest representation I’ve ever seen. Several dozen hardcore wounds on the Gothic statue’s body create clusters of blood clumps that could easily compete with bunches of grapes hanging in Leuk’s famous vineyards. Between the painful Christ and the skull wall – drapes in the color of blood.

It’s a thought-provoking setup: rows of chairs facing the skull wall, framed by dramatic red curtains. There’s a theatrical feel to it. Except, the choir pressed in the wall is not performing.

“When someone dies, they close the curtains”, Heidi revealed. “The coffin is displayed here before the funeral, for three days. People come and pray for the deceased.”

The red room that resurrected my “Twin Peaks” memories thus has a double function. Lynch house is also – a lych-house, a mortuary.

Beinhaus Leuk’s Danse Macabre – where do souls go after death?

Beyond the artfully displayed human craniums, the Beinhaus in Leuk offers a literal postmortal guidebook to the medieval mind.

On the eastern wall of the ossuary, the restored Poor Souls Altar from 1506 showcases the Mother of God sharing clouds with angels and baby Jesus. Below their unreachable rosaries, the desperate souls in burning hell can only pray. Well, without those flying broomsticks, there’s no escaping.

In the center of the room, the square pillar that was exposed together with the walkway behind it in the 1982 renovation, is much more than just the foundation of the middle bundle pillar of the church’s southern arcade. On the pillar’s southern and western walls, the Danse Macabre frescoes from 1520-1540 expose Death as a carrier of both young and old, rich and poor.

The Dance of Death scene on the western side of the pillar shows half-decomposed carcasses attacking a Pope, a cardinal, a bishop, a priest, an abbot, and an entire choir of clergy. The leading cadaver aims an arrow at the Holy Father while holding an hourglass with a hand stuck through the Pope’s triple crown. “The hour is here”, says the other strangler holding the cardinal’s hat and grabbing the Pope’s cloak. The clergymen stripped of their holy hats and stoles are a reminder that even the people of the Church won’t be spared of dancing with Death. Their spot on the “dance floor” may be closer to the altar, and they may not end up on the skull shelf, but in the end, everyone turns into dust.

The second picture, on the southern side of the pillar, features skeletons armed with arrows, scythe, and bare bony hands, attacking three gents on horses and their entourage. The fresco by the unknown German-Swiss artist demonstrates that no amount of armor or bribe can buy you mercy at the meet-up with the grinning Death.

This remarkable monument of Renaissance art that doubles as an oracle of surrounding bones and skulls, has a penetrating memento mori inscription: “What you are, we once were. What we are, you will become.”

History behind the Beinhaus of Leuk

Throughout its history, the Church of St. Stephan served as a religious center of the district, spreading its authority over 12 communes. That was a lot of parishioners, and over time – a lot of dead bodies.

The cemetery surrounding the church in the old days was small, so they had to recycle the plots. Unless you were a member of the church clergy or the patrician families, privileged to rest their bones inside the church, they’d give you 25 years to rest in peace. After that, your remains were evicted from the grave and stored in the ossuary chapel.

“In the 16th century, it was generally customary in Europe to keep bones like this after a short resting period”, Heidi said. The dead had to make way for the deader. The tradition resulted in some 20 catacombs in Wallis, with the one in Naters, 30 kilometers to the east, being another notable example.

Besides just tackling the problem of an overcrowded graveyard, Beinhaus Leuk had a religious meaning too. In times when lay people couldn’t read, the bone shelves made of people gone before us were serving as an illustrative reminder that the afterlife was coming with justice. Death awaited both rich and poor (even if Leuk Mummy and other nobles buried inside the church tell us that you really had to be illiterate to swallow the idea of no privileges).

The documents in the parish archives tell us that the bone-stacking in Leuk Ossuary began in 1505. The practice continued until 1860. In that three and a half centuries, between 22,000 and 24,000 people were reduced to the anonymity of bones.

While most of them were farmers, some died of violent death. Scars and bullet holes in some skulls tell us tragic stories of poorly equipped mountain soldiers who couldn’t fend off the troops of the French Revolution, during the Battles of Pfyn in 1798 and 1799.

As I pondered on this war that swiped two-thirds of all German-speaking men in the canton, the doors of Leuk Beinhaus creaked open, and laughter dropped a visit. Four young women, giggling in French, headed behind the red curtains and started poking the skulls as if they were testing tomatoes at the supermarket. The fallen parishioners were again defenseless. Not much had changed since 1798.

Why did they hide Leuk Charnel House behind the wall?

Several theories try to explain why the Ossuary of Leuk was hidden behind the plaster wall, probably in 1886/1887.

Theory 1: Skull snatchers

In the latter half of the 19th century, there was no more shortage of vacant plots in the cemetery, so the dead didn’t need to be evicted. On the other hand, the skulls that were already displayed in the bone chapel were an open invitation to mischief for the local youth (I’m telling you, humans don’t change rapidly). Supposedly, students from wealthier families would return to Leuk for summer break, and kill their boredom by stealing skulls. So the church decided to build the wall.

Theory 2: Erasing the eerie

Another widespread theory says that the people of the 19th century simply didn’t want to look at skull walls anymore. So they erected plaster walls in front of them and pretended the skulls were never there. After a century or so, nobody even remembered they existed. Out of sight = out of mind.

Theory 3: The enigma of iconoclasm

A retired teacher and local guide André Ruffiner once suggested that Leuk skulls and sacral statues might have been concealed during the Reformation, to protect them from the iconoclasts. However, the most significant Swiss icon-smashing riots occurred in the first half of the 16th century. So it is not clear how would this theory explain the accumulation of so many skulls in such a short period, from 1505 to 1520s.

So, the real reason Beinhaus Leuk decided to build that plaster wall in the late 19th century remains shrouded in mystery.

Beinhaus Leuk Mystery – Conclusion

Our ancestors were capable of taking better care of the dead, even if it meant resorting to fake walls and misleading cabinets, the medieval version of Narnia.

Whether the bones and skulls of Leuk’s ossuary were exhumed from some colossal mass grave, or their accumulation was simply a side effect of a pressing cemetery space issue, they were treated with respect. Lined up in neatly arranged rows, they shared the stage with the church’s most precious artworks.

The ossuary concept skins everyone to sheer bones, devoid of gender, race, nationality, or social status. But Beinhaus Leuk fails to prove the point of its frescoes – that death doesn’t discriminate.

Today, Beinhaus Leuk watches over its skulls with nothing more than a feeble surveillance camera warning. That doesn’t deter certain visitors from treating someone’s resting place like a haunted house playground. These reckless tourists touch the skulls for their amusement, or even bring them home like souvenirs, seemingly without consequences.

On the other hand, down in the crypt of St. Stephan’s Church, the Mummy of Leuk and the sacral art recovered from the heaps of bones are locked away. So securely, that the mere touch of the barred door could set off alarms. For the lock of hair taken from the late Pope John Paul II as a relic to venerate, even the location is kept a secret.

This is an eye-opening contrast that confirms the contradictions of the modern Church: it doesn’t always follow what it preaches.

The ossuary that as a concept skins everyone to sheer bones, devoid of gender, race, nationality, or social status, fails to prove the point of Beinhaus Leuk’s frescoes – that death doesn’t discriminate.

The two-digit number of VIP graves inside the church shows that not everybody had to see the graveyard as a temporary buffet for microorganisms and parasites, after which one is doomed to an anonymous wall decor in a dimly lit 50-square-meter basement.

Nameless and forgotten, the thousands of skulls framed by those dramatic red curtains of Leuk’s Beinhaus rightfully resemble just a scenography. Such are bones, they do not object to how anyone treats them. In the living, their main function is to protect the organs. But who will protect the bones?

Visiting Leuk Ossuary – Quick Info

How to get to Beinhaus Leuk

The Beinhaus Leuk is located in the town of Leuk, in southern Switzerland. The town is about an hour’s drive from Bern.

There are convenient train services to Leuk from different parts of Switzerland. Once you are there, grab bus no. 471/472/473/474/475, right outside the train station, for a short two-stop ride to the town center. From there, the ossuary is 300 meters downhill, easily strolled with the help of Google Maps.

Where to stay in Leuk

Most of Leuk’s touristic infrastructure is located in the resort village of Leukerbad, the hot spot for thermal spas.

If you fancy a stay in excellently-rated hotels with their very own baths, pick between the luxurious 5-star Hôtel Les Sources des Alpes, the traditional 4-star hotel Le Bristol Leukerbad, or the modern Therme 51° Hotel Physio & Spa. Follow the links to find the best price for your travel dates!

Leuk Charnel House tickets

There is no entrance fee to the charnel house in Leuk. You can explore the location at your own pace, free of charge.

Beinhaus Leuk opening hours

The Leuk Charnel House is open year-round. The ossuary doors welcome visitors between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. Exceptionally when someone dies, their body will be laid out in the coffin for three days at the ossuary, and in that period Leuk’s skulls will be out of sight.

Beinhaus Leuk Tour

From July to late October, Leuk Tourismus organizes free guided tours of the town, including Beinhaus Leuk. The tours are scheduled every Tuesday, at 2:30 p.m., and the meeting place is in front of the Leuk Town Hall (Rathaus). English may be in short supply, so bring your pantomime skills!

Did you like this guide to Beinahus Leuk, the fascinating charnel house in Wallis?

Pin it for later!

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning if you click on them and make a purchase, Pipeaway may make a small commission, at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our work!

This is the kind of place I would travel for. Churches have some amazing architecture and stained glass windows. But, this history is beyond fascinating. I’ve done the catacombs tour in Paris, but this is a whole new level. I am also fascinated by the Valais witch trials and want to learn more. Great piece!

Hi Alexa!

I’m happy that you enjoyed the article.

Beinhaus Leuk is indeed a captivating place with a unique blend of history and mystery.

It offers a fascinating perspective on church crypts and the stories they hold.

For Valais witch trials, I’d be happy to do further research myself too.

Here’s an interesting fact that caught me by surprise: Did you know that the majority of those early witches burned by the Church were – male?

I wonder when did that shift toward women as prime devil’s associates actually happen.

I would have never guessed that most of the witches burned were male. This does deserve some research!

Well, at least in those early days, it was like that. Apparently, two-thirds of accused/condemned Valais withes were – men.

I think it was similar in Iceland, so perception of women as witches shifts with geographical/cultural landscape (and time).

I would have loved to have seen this and am surprised I had no idea about it when I was in Switzerland. It’s so unique. How long did it take to tour?

Hi Heather!

While not as well-known as some other Swiss attractions, Beinhaus Leuk is a special place, but not huge.

Depending on your pace and the level of detail you want to explore, I believe the entire church visit could take around 30 minutes to an hour.

Of course, if you’re deeply interested in the history and art this place holds, you can certainly spend more time.

Without an English-speaking guide or English-written signs, even Google Translate bites off some minutes 🙂

If you ever get the chance to visit again, it’s definitely worth a visit.

If it becomes too macabre, you can always brighten up your day in the thermal baths of Leukerbad, the village further uphill.

Safe travels!