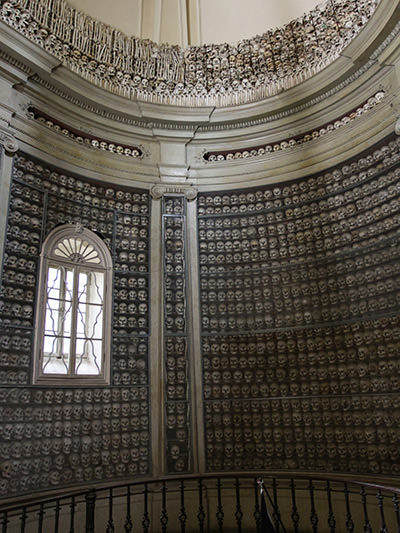

In the apse trimmed with white drapes, as in some anti-version of a live theater spectacle, a choir of heads silently stares. Human skulls, erased of identity, cover the curved wall of this church in Northern Italy from bottom to top. Ossuary of Solferino is a final resting place for soldiers who lost their lives in a decisive battle of the Second Italian War of Independence.

Long after the death of Solferino soldiers whose remains are displayed in the ossuary, our “civilization” would proudly continue to roll countless skulls down the war bowling alley

This death-sowing 19th-century combat was so brutal and bloody that it inspired Henry Dunant to write “A Memory of Solferino”, an influential book that would later bring him a Nobel Peace Prize, the first ever. Monstrosities of that war directly called for a more humane world, in which the Geneva Conventions and the International Red Cross would be established.

The Battle of Solferino happened on June 24th, 1859. While entering this quiet ossuary with unburied remains of the thousands, I couldn’t ignore the fact that I was born exactly 120 years later.

If we would play naïve, we could fantasize that I came into a better world, an upgraded society that learned historical lessons. But long after the death of Solferino soldiers, and the death of Dunant himself, our “civilization” would proudly continue to roll countless skulls down the war bowling alley.

Only in the first eight months of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, between 70 and 120 thousand lives were lost. It would take more than a dozen ossuaries to display our newest bones collections.

In a horrific world as it is, the memory of Solferino fades away.

Why was the Battle of Solferino so important? What exactly happened in this small village in Lombardy in 1859? Who fought, who won, and who got defeated? Read the full story of two regional charnel houses, the Ossuaries of Solferino and San Martino!

The oldest human skeletons, such as Lucy in Ethiopia, are preserved by pure luck. In this African region, there is a natural predator whose stomach acids dissolve even bones - the hyena!

Ossuaries backstory: Who fought the Battle of Solferino?

The Battle of Solferino was a crucial episode in an attempt to unify the Italian states (the so-called Risorgimento of Italy). On one side, there was Piedmont-Sardinia, joined by the allies from France, and on the other – Austria.

Solferino Battle was the last major world conflict in which monarchs personally commanded the troops, which certainly contributed to the bloodshed. Without experienced military professionals, the French Army was led by Napoleon III, the Piedmont-Sardinian Army by Victor Emmanuel II, and the Austrian Army by Franz Joseph I.

Emperors brought troops into an unexpected, accidental clash. The chaotic and uncoordinated battle took place just south of Lake Garda, near the villages of Solferino (where the French confronted the Austrian corps) and San Martino (where the Piedmontese bumped into the Austrian right wing).

While the Franco-Sardinian Alliance claimed victory, and it did lead to the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, soldiers treated as cannon fodder came as a screaming cost of the nation-state.

How many people died in the Battle of Solferino?

Historians have different estimates of the number of soldiers fighting in the Battle of Solferino. These can range from anything between 180 and 400 thousand, but most agree that the number was more probably 250-300 thousand.

The first official reports talked about less than 5.000 dead in the half-day-long slaughter. But when the bodies were exhumed from the battlefield in the 1870s, the Battle of Solferino’s casualties grew to more than 20,000. Some experts even double this number.

Over several centuries, one Swiss ossuary collected 22,000 skulls, managed to hide them, and then forgot all about them! Learn the fascinating story of Leuk's secret charnel house!

How did the idea of the Red Cross start?

Henry Dunant (Jean-Henri Dunant) was a Swiss businessman who came to Italy to obtain Napoleon’s approval for exploiting water resources in Algeria. But what he ended up experiencing was the horror of war.

Thousands of instantly killed on the battlefield, thousands wounded and then unscrupulously executed, thousands dying with no access to medical help…

The French army, for example, had more veterinarians than doctors. The lives of humans who were not capable of fighting anymore seemed to be disregarded as useless.

Shocked by the suffering, Dunant stayed in Solferino to organize medical treatment for the survivors, regardless of their nationality. It was here that the phrase “tutti fratelli” (all brothers) was coined.

In 1862, Henry Dunant published “A Memory of Solferino”, a graphic report of the battle he used as a tool to convince political heads of Europe that something needed to change. His lobbying efforts led to the founding of the Red Cross, as well as the setting of the Geneva Conventions, the protocol for humanitarian treatment in war.

If you want to read the war report by the father of modern humanitarianism, you can order “A Memory of Solferino” here, in paperback, hardcover, or Kindle version.

Ossuaries of Solferino and San Martino – keeping memories with dignity

Due to a large number of fallen soldiers scattered over the fields of Solferino and San Martino, proper burial was impossible. To prevent the smell, they were all just quickly covered with soil in wide ditches.

A mass grave was not the most hygienic solution in the long run. However, for epidemiological reasons, health legislation allowed the exhumation of dead bodies only when 10 years have passed from the burial.

In 1870, the remains of the corpses were dug out and respectfully placed in two charnel houses. A church in Solferino and a chapel in San Martino became the final resting places of soldiers from both sides.

Italians love to display human remains, even when they belong to a patron saint of love. Here's where to find St. Valentine's skull in Rome!

Ossuary of Solferino

Slightly uphill above the street it lent a name (Via Ossario), the Ossuary of Solferino is in the heart of a little cypress forest that envelops a gravel path leading to its entrance.

The first neighbor of the Museo Risorgimentale di Solferino, the ossuary offers another perspective on the resurgence.

Originally, it was a parish church, the oldest prayer house in Solferino, but during the 1859 battle, it got severely damaged. War wounds on the Church of San Pietro healed over a decade, and in 1870, the renovated building opened up as an ossuary, a home to the remains of 7,000 soldiers.

The church entrance is still marked by a mosaic of a saint it is dedicated to (Saint Peter), joined by a mosaic of Christ below, and a statue of Madonna above. On the right-hand side of the entrance, there is a memorial plaque honoring Henry Dunant’s idea of the Red Cross, with a famous sentence “Inter Arma Caritas“ (Among arms, charity).

The interior first starts with black busts of the French generals that quickly get overshadowed by a staggering wall of skulls in the apse.

The crypt reveals more neatly displayed bones, under the national flags of France, Austria, and Italy.

The side altars also hold cages of bones stacked on shelves, organized according to type.

Behind the bars of two additional rooms, one can see complete skeletons, and more partial skulls and bone collections.

Ossuary of San Martino

Also at Via Ossario, but in the village of San Martino, once an ordinary chapel that belonged to the Santa Giulia monastery in Brescia, and dated back to at least 1042, became a charnel house in the 19th century.

In rural surroundings, a path lined with trees, memorial stones, and monuments to battalions and brigades leads to the ossuary chapel of San Martino della Battaglia. Its exterior walls are adorned with plaques remembering the figthers for Italian unification.

Behind and bellow the chapel’s altar, the remains of fallen individuals from both sides are displayed. The apse contains 1.274 skulls stacked on top of each other, while the crypt topped by an iron railing holds the bones of 2.619 soldiers.

One can learn more about the battle on the other side of the road, where a museum and a memorial tower have been erected.

Just like its counterpart in Solferino, the Ossuary of San Martino is also nestled in a quiet area, far away from the usual tourist interest, providing a peaceful place for reflection and contemplation.

Entry to both ossuaries is free of charge, but one can leave a donation at discretion.

Where to stay in Solferino and San Martino? If you are looking for a place to stay in the vicinity of the ossuaries, the following are your best options. In Solferino, consider booking a family-run Hotel Ristorante Alla Vittoria dating back to 1909, Locanda All'Avanguardia set in a 1920s building, or a newer Affittacamere Residenza Del Duca. In San Martino della Battaglia, find your bed in a 19th-century building of Cascina Le Preseglie, rest by a modern pool at BeBDoremi, or opt for a farm stay at Agriturismo Almavite. Follow the links to find the most recent prices and property photographs.

Ossuaries of Italy – Conclusion

Just a few kilometers south of Lago di Garda, more known for the lively streets of Peschiera del Garda and the so-called death train of Gardaland amusement park, there is a rather different perspective on life and death.

Far enough that typical touristic noise, screams, and laughter completely die out, rows and rows of silent human skulls wait to be seen.

Our memory is a construct, and we naturally prefer to fill it with events that will not disturb us.

When Henry Dunant wrote “A Memory of Solferino”, he aimed to do exactly the opposite. He disturbed his readers and made them change the ways we fight wars.

Red Cross and the Geneva Convention are, however, just small victories in our arming-obsessed era. Dunant lived before the 20th century saw conflicts on a global scale, and before the 21st century continued developing advanced weapons as if we were expecting to attack extraterrestrials and not our first neighbors.

Under our war uniforms, we are all the same bones and marrow

Ossuaries of Solferino and San Martino are not just resting places of no-name soldiers, sacrificed for the greater good as decided by their leaders. These charnel houses are also deeply moving monuments. They remind us that under our different skins, war uniforms, and national flags, we are all the same bones and marrow.

Stacked together on shelving, just like soldier bodies previously on the battlefield, the skulls of Solferino and San Martino have no nationality. They are bare witnesses to the senselessness of wars.

There are no winning and losing armies once we turn to dust.

What are your thoughts on ossuaries, these churches made out of bones?

Leave your comments below, or pin this article for later!

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which means if you click on them and make a purchase, Pipeaway might make a small commission, at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our work!