Basel, where three countries meet, has always been a crossroads of culture. This May, the Swiss city hosted the Eurovision Song Contest, thanks to Nemo’s victory in Malmö a year before. Music fans could have spent days just exploring the ESC locations. But the same is true for some forty (40!) museums that call Basel home. Among them, Kunstmuseum Basel, the first public museum in the world, houses the most prestigious art collection in Switzerland.

What if we gave each song a canvas twin? Eurovision provided acts, Kunstmuseum gave us centuries of mood, metaphor, and abstract nudes

Available to visitors since 1671, this grandiose Museum of Art displays a wide range of works, from Renaissance masters to modern and contemporary art. Basel Kunstmuseum exhibitions regularly feature impressionists and post-impressionists such as Vincent Van Gogh, cubists such as Pablo Picasso, or expressionists like Oskar Kokoschka. Kunstmuseum in Basel also loves to shine light on overlooked revolutionaries, like the current retrospective on Italian-French sculptor Medardo Rosso.

With Eurovision fans, often prioritizing glitter and spectacle, storming Basel in feather boas and flag capes, you’d be forgiven for thinking it was a culture clash waiting to happen. High art vs. high camp. Exhibitions vs. exhibitionism. Two hardly connected worlds, right?

But what if we gave each song a canvas twin? Eurovision provided acts, Kunstmuseum gave us centuries of mood, metaphor, and abstract nudes. What do we get if we put them together?

From Käthe Kollwitz’s grief-stricken mothers to Penck’s fire-stick men, I matched this year’s performances with Kunstmuseum Basel artworks that felt just right. Some are perfect fits. Others are… interpretive. Much like Eurovision itself.

Check out these museum-music match-ups!

Baby Lasagna performed in the Basel Eurovision's pre-show. During the act, a series of visual glitches appeared, some referencing web art pioneers, others distributing Islamic struggle messages. Is this the newest Eurovision controversy?

Eurovision meets Museums. Or does it?

When Basel City proposed a free press tour of the cutting-edge Vitra Design Museum and the surrounding architecture campus, I was the only journalist (among hundreds!) who showed up. With a question mark above my head: did Eurovision fans not care for art beyond their bubble?

A few days later, a guided tour of the Kunstmuseum, one of the best museums in Basel, attracted a dozen media colleagues, restoring hope that centuries of art could still provide meaning.

After an hour of exploring the highlights of the Kunstmuseum Basel collection in the media group, I decided to linger and roam the place on my own.

With Eurovision goggles on, I tried to determine whether centuries-old Kunstmuseum Basel artworks could speak to today’s Eurovision crowd.

My visit turned into an exciting curatorial game. Eurovision is alive and well among Kunstmuseum Basel masterpieces. You just have to know where to look.

Where to stay near Kunstmuseum Basel? Located just 200 meters from the Kunstmuseum Basel, Nomad Design & Lifestyle Hotel offers a modern and urban atmosphere. Housed in a classic 1950s building, the hotel features individually furnished rooms, a lively restaurant, fitness center, and sauna. Guests benefit from amenities like free Wi-Fi, complimentary bicycles, and a BaselCard for free public transport. There’s even a Library Club. Book this hotel through your preferred platform: Booking, Agoda, Trip, and Expedia. Another hotel providing convenient access to the Kunstmuseum Basel, some 500 meters away, is Motel One Basel, in the heart of Basel’s Old Town. This budget-friendly design hotel offers modern rooms, a 24-hour front desk, and a stylish bar. Guests appreciate its central location, close to major sights and public transportation hubs. Book this hotel through your preferred platform: Booking, Agoda, Trip, and Expedia.

What to see in Kunstmuseum Basel

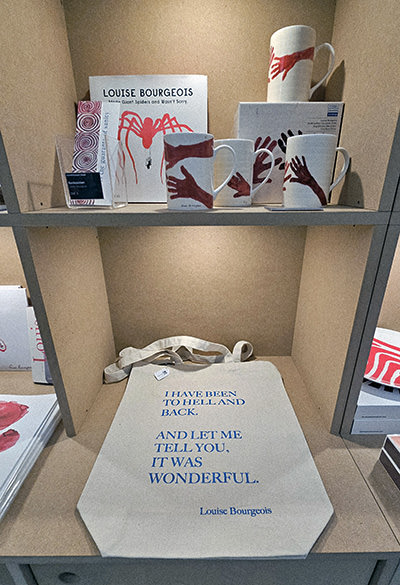

Kunstmuseum Basel shop

Every good museum visit should either begin or end at the gift shop. Preferably both.

At the Kunstmuseum Basel shop, my eye was immediately drawn to a shelf of linen tea towels – the signature creations of Glasgow-based visual artist and cheeky contrarian David Shrigley. Made by Third Drawer Down, these products can function both as posters and as, well, towels.

The illustrator rose to fame by poking fun at the pretensions of art-world seriousness dictated by schools. One of his towels simply reads “Be nice”, softened by a rainbow.

It brought to mind an oddly relevant moment from this year’s Eurovision. When the contest’s Media Handbook asked journalists to “be respectful” and not damage anyone’s image, some cried censorship. Managing Director Martin Green dismissed the interpretation that this goes against the freedom of the press, and translated their request as: “Be kind.” He would’ve probably loved to dry his washed hands with D. Shrig towels.

Over in the Kunstmuseum Neubau (the 2016 extension of Kunstmuseum Basel), another gift shop offers more merchandise gems. One tote bag declared: “I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful.”

Wait, didn’t the verses go “I, I went to hell and back, to find myself on track”?

The bags were not quoting Nemo, a non-binary Eurovision winner, but Louise Bourgeois. The French-American artist also dealt with themes of sexuality, trauma, and fear of rejection. And, for her, sculpting was a form of exorcism, a way to discharge emotions through art.

Finding Nemo at Kunstmuseum Basel

Our guided tour through the highlights of the Kunstmuseum Basel artworks began before a chilling oil-and-tempera painting – “The Dead Christ in the Tomb” (1521-1522). German artist Hans Holbein the Younger (whose works formed the base of the Kunstmuseum’s collection through the Amerbach Cabinet) painted Christ’s lifeless body in a horizontal format, with such an unsettling realism that devout viewers might instinctively clutch their rosaries.

Christ’s hand, frozen in decomposition, appears to extend a middle finger – whether toward the heavens or humanity is open to interpretation. The macabre artwork even appeared in Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot”, questioning the power of religion over nature. As Prince Myshkin says in the novel: “A man could even lose his faith from that painting!”

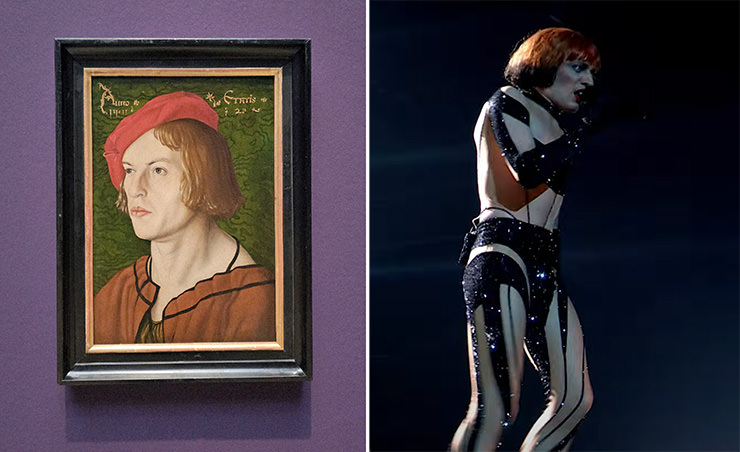

But my Eurovision-senses began to tingle just next door. In a quieter corner of Renaissance grandeur, hung the “Portrait of Jakob Meyer zum Pheil of Basel” (1511). Attributed to an Upper Rhine master from Hans Baldung Grien’s circle, the painting showed a man from a noble family of Basel cloth merchants, the youngest son of Nikolaus Meyer zum Pheil, a 15th-century Mulhouse mayor.

Now, some might argue that Nemo’s “The Code” owes more to the “Diva Dance” in “The Fifth Element” than to anything painted before the electricity. Even their Eurovision interval act “Unexplainable” continued to explore the same sci-fi universe and interdimensional vocals, with the Leeloo-style orange wig, of course.

But as I squinted in front of the Renaissance portrait of the prominent patrician Mr Jakob, I couldn’t help but reflect that, if Nemo did travel through time, they might not have gone forward, to the 23rd century, but backward, to the 16th.

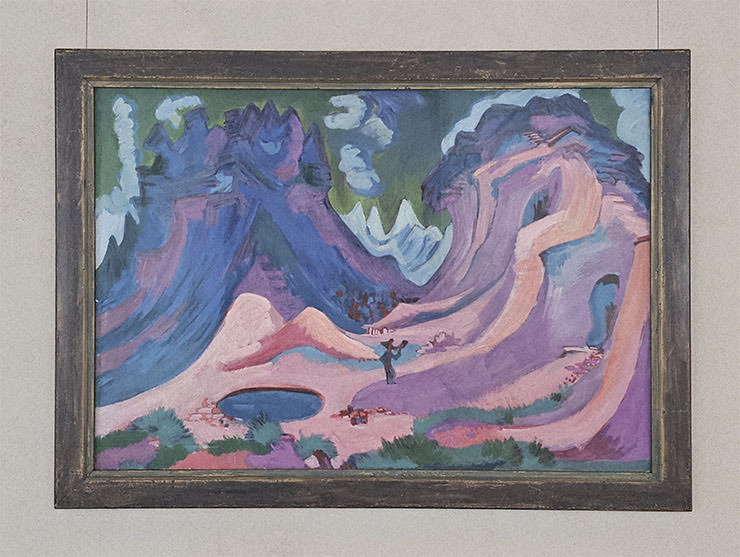

Staging the Eurovision scene

If you watched Basel Eurovision, you remember the centerpiece of St. Jakobshalle was a showstopper stage with a mountain-inspired design. Following the idea of Florian Wieder (his ninth stage design for Eurovision), a giant LED screen showed alpine peaks pulsating in pink, red, and light blue colors.

Naturally, when I stumbled upon the “Amselfluh” (1922) in one of Kunstmuseum Basel’s corridors, I couldn’t unsee it. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s oil on canvas portrayed a vivid mountainous landscape in vibrant colors that saturated the intense scene with a sense of dramatic movement, in a similar way that digital Eurovision hearts did to its stage mountains.

In the center of the painting, a lone human figure blows a horn, anchoring us in the surreal panorama.

Then it hit me: the 2025 Eurovision Song Contest was not just opened on a stage with a similar color palette, but the main music act of the opening was Lochus Alphorn Quartett, a group that summons the spirits of the Alps with their traditional wooden wind instruments.

Just like Wieder, Kirchner was also German, but one whose work Nazis labeled as “degenerate”. Despite many of his works being destroyed, the co-founder of Die Brücke remains remembered as one of the most influential figures of Expressionism.

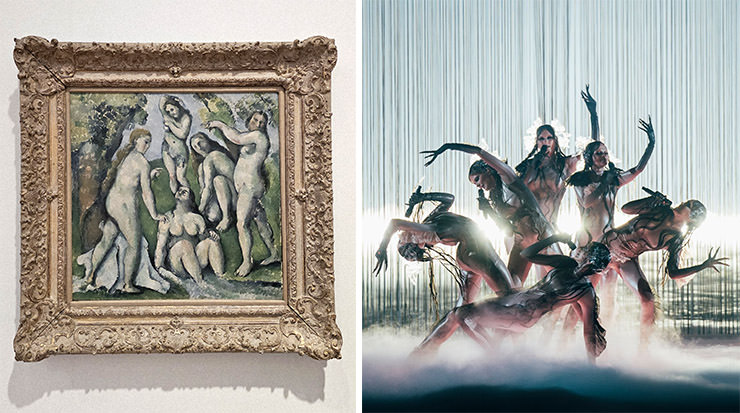

View to Infinity (Ferdinand Hodler) & Five Bathers (Paul Cézanne)

Climb the grand staircase of Kunstmuseum Basel and you’re rewarded with a view that’s – quite literally – infinite. The large-scale painting was initially created for Kunsthaus Zürich (1913-1916). However, the monumental dimensions of “View to Infinity” (9 x 4.5 meters) wouldn’t fit the original destination, so Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler had to make a new version for Zurich. Basel graciously hosted the big one.

The painting features five women standing before a curved horizon in flowing blue robes, gazing into the distance. It shows the human contemplation of the universe, searching for meaning through meditation. The cosmic calm they channel feels worlds away from Eurovision. Or is it?

Tautumeitas, Latvia’s Eurovision entry, created probably the most transcendental experience during the entire competition. The Baltic queens of ancestral chant polyphony turned the stage into a ritual site, inviting us into a sonic trance of layered harmonies and cultural heritage pride. Their “Bur Man Laimi” performance felt like a spiritual séance wrapped in folk couture, which, in retrospect, could easily hang next to Hodler’s mystics-in-robes.

Swiss art historian Oskar Bätschmann once compared “View to Infinity” to Paul Cézanne’s “Large Bathers”. Exactly in front of Cézanne’s oil on canvas “Five Bathers” (1885-1887), from the same series that explores human figures in a landscape, did I think of Latvia’s Eurovision act again.

In Post-Impressionist style, five nude women blend into nature without precise details in their faces and bodies. The artist ditched realism in favor of abstraction, marking a crucial turning point in art history that questioned the very nature of painting.

Similarly, the mesmerizing performance of “Bur Man Laimi”, with hypnotic rhythm and earthy tones that remind of Cézanne’s Bathers, enchanted the audience by avoiding individual portraiture of the singers, and focusing on the harmony and feminine mystique they brought as a collective.

Latvia landed 13th, right in the middle of the scoreboard. Not quite infinity, but far from zero.

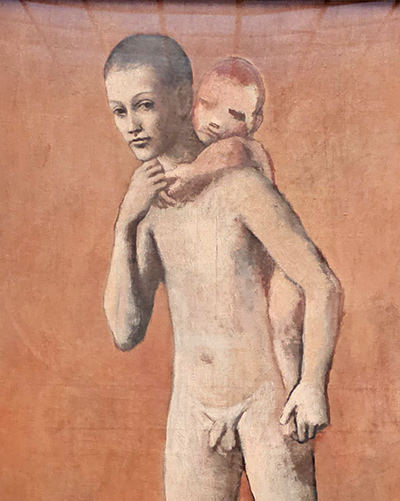

The Two Brothers (Pablo Picasso)

One of the most iconic Kunstmuseum Basel artworks is Picasso’s “The Two Brothers” (1906). This oil on canvas captured two nude boys, the older one carrying the younger on his back.

Picasso painted this piece during his stay in the village of Gósol, on the Spanish side of the Pyrenees, where earthy Catalan influences softened his brush. He rendered the two figures in gentle contours and muted reds.

“The Two Brothers” was one of the two paintings (“Seated Harlequin” being the other) whose owners, faced with financial difficulties, decided to sell them in the 1960s.

Refusing to lose the loaned artworks, Basel taxpayers voted to save them in the 1967 referendum (yes, for real!), and fork out 6 million Swiss francs. The citizens had to contribute the rest; they went out to the streets, organized now-legendary Bettlerfest (Beggar’s Festival), and raised an additional 2.4 million francs with performances, selling goods, and shaking donation cans. Touched by the Baslers’ passionate fight, Picasso gifted the Kunstmuseum Basel four more artworks.

The younger, flame-haired brother in the saved painting from the artist’s Rose Period (phase when he swapped blue melancholy for warm tones, tender friendships, and a hint of circus optimism) is a spit image of Belgium’s Eurovision entrant: Red Sebastian.

The rouge-tinted and vocally impressive Seppe Herreman (Red Sebastian’s civilian alias) lit up the stage with “Strobe Lights”, but sadly didn’t make it past the Semi-Final – the Eurovision equivalent of failing a public referendum.

Woman with Hat Seated in an Armchair (Pablo Picasso)

Another of Picasso’s artworks housed in the Kunstmuseum Basel is “Woman with Hat Seated in an Armchair” (1941-1942). The portrait with fragmented, angular forms, blending Cubism and Expressionism, is believed to represent Dora Maar, Picasso’s lover and a frequent subject in his paintings during the dark days of World War II.

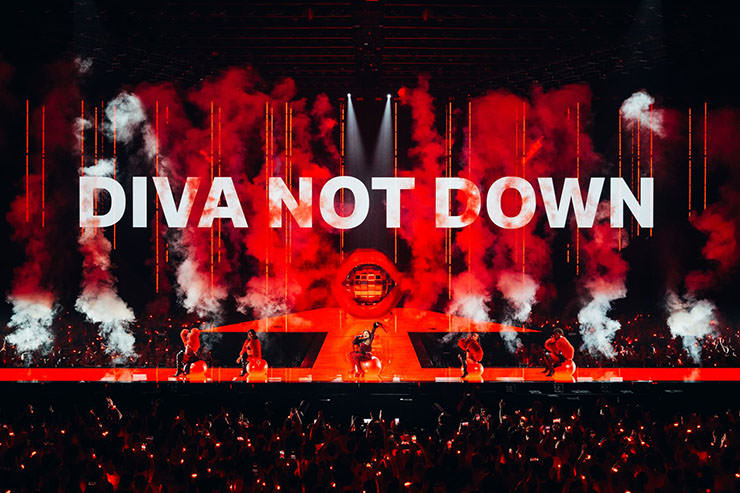

Equally elegant, in an introspective pose, and with the interplay of light and shadow, a pop artist from Picasso’s homeland started her dynamic performance at the Swiss Eurovision. Melodía Ruiz Gutiérrez, or more condensed – Melody, brought “Esa Diva” to the Basel stage, an act bursting with Spanish flair and theatrical energy.

Melody’s woman-empowering show might have started like a pose, but unlike Picasso’s muse, she refused to remain in a frame. The singer tore through the curtain, delivered a quick-change act, from black to silver, and a bold choreography that only supported her vocal power. This diva paints herself!

While Melody didn’t climb high on the scoreboard (24th, with 37 points), her charismatic stage performance left an imprint – an act of rebellion against stillness, against reduction. Much like Picasso’s postwar portraits, Esa Diva was fragmented, expressive, raw. And impossible to ignore.

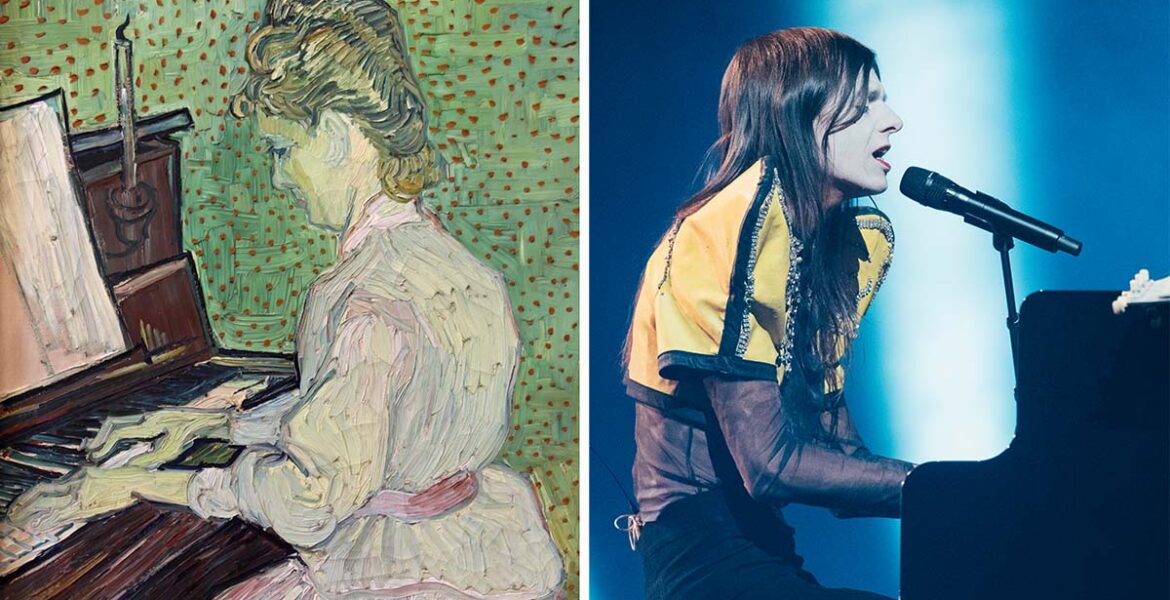

Marguerite Gachet at the Piano (Vincent Van Gogh)

“Marguerite Gachet at the Piano” (1890) is another portrait of a seated woman quietly hanging at the Kunstmuseum Basel. Here, a lady in a rose-colored dress is caught mid-melody, fingers on a dark violet piano, against a green wall with orange spots. The characteristic expressive brushwork on this double-square oil on canvas is unmistakable – it is one of the last artworks of the famous Vincent Van Gogh.

Marguerite was a 21-year-old daughter of Dr. Paul Gachet, the physician who cared for Dutch artist in Auvers-sur-Oise, a village where Van Gogh spent his final months. The young woman in the painting appears distant and detached, concentrated on the piano, and radiating a certain melancholy.

Also featured in a semi-profile view, with a white-painted face and emitting a similar introverted gloominess, Italy’s Lucio Corsi opened his Eurovision performance of “Volevo essere un duro” (“I Wanted to Be Tough”) while playing the keys on the piano. Or, well, pretending to play them.

In 1999, instrumental music was expelled from the contest when Israel decided to avoid spending money on an orchestra. Other broadcasters followed suit, establishing a backing track as a golden standard of Eurovision, where instruments were reduced to props.

Lucio broke the fourth wall of Eurovision convention by integrating a mouth organ (harmonica) into the voice microphone, and thus entered history as the first ESC act in this millennium to play an instrument live.

The song landed a respectable fifth place in the Grand Final.

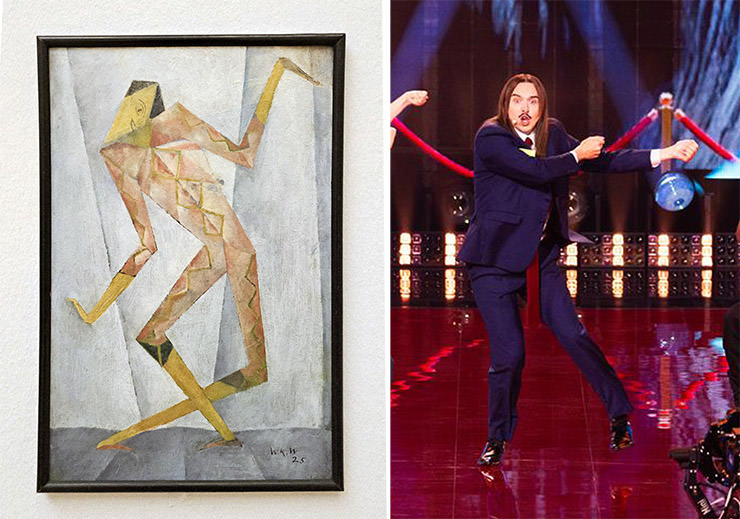

Harlequin (Walter Kurt Wiemken)

In a Kunstmuseum Basel room echoing with circus motifs, a vibrantly strange “Harlequin” (1925) stood out. This is an artwork by a Basel-born painter, Walter Kurt Wiemken, known for his contributions to Expressionism, Impressionism, and Surrealism.

The painting of a trickster with hair parting blended influences of all three while portraying a classical figure that embodies theatricality and disguise. The harlequin appeared fragmented, with a brushwork that bordered on the childlike, reminiscent of Paul Klee’s sketch-like universe.

With signature dance moves that looked as if someone had prompted AI to generate a video from an image (and used “Harlequin” as that image, of course), Tommy Cash represented Estonia at Eurovision 2025 with an absurdist satirical song “Espresso Macchiato”.

Tomas Tammemets’s eccentric alter ego, with exaggerated coffee-fueled footwork, supported a modern-day harlequin act, a disorienting chaos fit of Wiemken’s Espressionism universe. They both reflected on identity and disguise, serving a protest against conservative trends in the arts.

Europe seemed to love it. Tommy Cash finished third in the Grand Final – proof that, at Eurovision, there’s always room for something disjointed.

Girl With Long Hair (Adolf Dietrich)

“Girl With Long Hair” (1930) is an important piece in the artistic legacy of Adolf Dietrich, a self-taught Swiss painter associated with Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) – a German art reaction against Expressionism.

This naïve art painting features a young girl gazing forward, her long hair flowing, rendered with soft but precise brushstrokes. The composition celebrates stillness and simplicity, capturing a subject’s presence without excessive embellishment.

In a very similar fashion and quiet intensity, Zoë Më took the Eurovision stage for Switzerland. Filmed in one uninterrupted shot, the performance of her introspective ballad “Voyage”, with cinematic setup and soft lighting, evoked an atmosphere of solitude and intimacy, supporting the singer’s delicate tone.

One doesn’t have to fulfill Eurovision’s maximum quota of six people on stage to leave an impression. Sometimes, less is indeed more.

And yet, Eurovision is often a party, not a gallery. The juries appreciated Zoë’s restraint, enough to push her into 10th place overall. But televoters? Not a single point. Maybe minimalism doesn’t text.

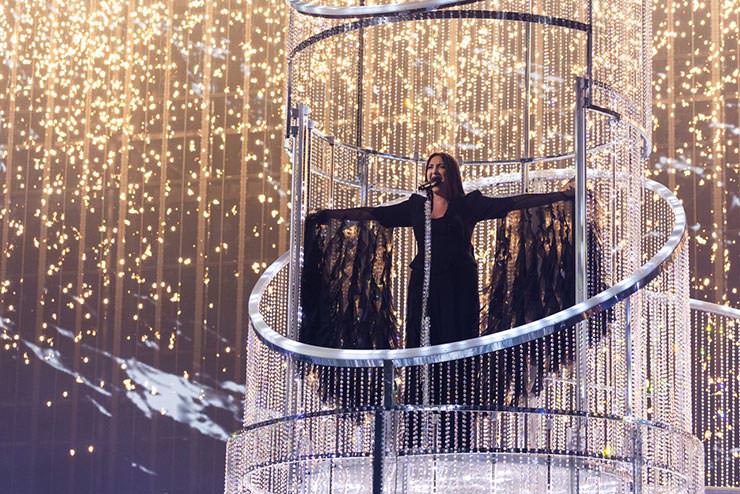

Girl on the Balcony (Georg Schrimpf) & War Picture (Maly Blumer)

Among the leading figures of Weimar Germany’s Neue Sachlichkeit art movement was Georg Schrimpf. As he belonged to the “right wing”, he managed to float under the radar of Nazi censors who interpreted his art as a tolerable form of German Romanticism. But his socialist past caught up with him; his professorship was revoked, and his works were branded “degenerate”, removed from museums and public life.

“Girl on the Balcony” (1927), gazing into the distance, seemingly lost in thought, fits Schrimpf’s serene, dreamlike realism. As if caught between the private interior world and the vast openness beyond, this quiet contemplation on the balcony represents introspection and detachment, where emotional excess is rejected.

When Yuval Raphael took to the Eurovision stage for Israel with “New Day Will Rise”, she too stood on a balcony – albeit a much shinier one. Perched on a glittering chandelier structure, the staging was an artistic nod to the balcony where Theodor Herzl, the father of Zionism, posed during the 1897 Zionist Congress in Basel. Yuval didn’t just stage the foundation of the Zionist movement in crystal stones at Eurovision; she even went to the original balcony to recreate the photograph that started it all.

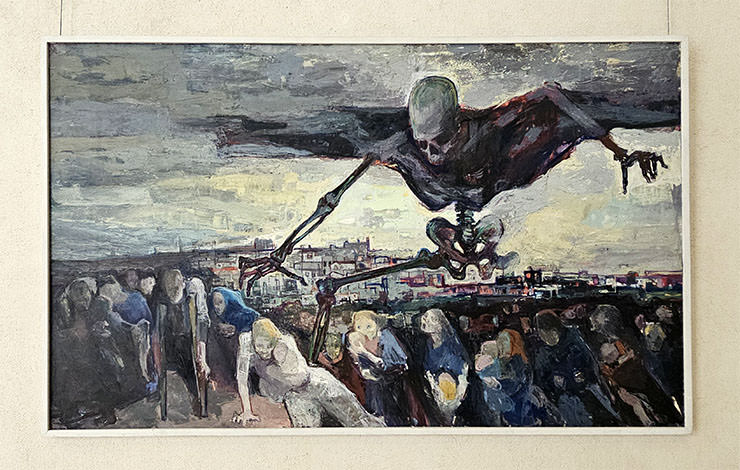

To understand the full gravity of Israel’s performance, there is a painting in the Kunstmuseum’s fundus that perhaps connects better with the decision to bring a survivor of the Nova music festival massacre as a Zionist mascot to Basel, delivering an overtly symbolic, politically charged message.

Maly Blumer-Marcus, a Basel native who initially painted still lifes, later explored human experiences and darker, conflict-related subjects. Her “War Picture” or Kriegsbild (1930-1975) is a deeply haunting portrayal of human agony. A monstrous figure of Death, with an oppressive, predatory aura, spreads its wings over an unidentifiable mass of victims, conveying a wartime trauma and a sense of hopelessness.

While Blumer likely depicted displacement and despair in the Second World War (just as her 1939 painting “Refugees on the Run”), the landscape suffocated with smoke in the “War Picture” is eerily universal. One might easily see a silhouette of Gaza as Dresden, with a deadly bomber flying over it.

So perhaps Israel’s 2025 Eurovision act wasn’t just another girl on a balcony, “seemingly lost in thought”. Perhaps it was closer to Blumer’s vision: a stage cloaked in politics, asking a continent to look – or look away.

“New Day Will Rise” rose to the second place at Eurovision, thanks to televotes.

Still wondering why Israel is in Eurovision? Read on!

The Shipwrecked (Heinrich Altherr)

Just a few steps from “War Picture” – as if Kunstmuseum Basel had anticipated a Eurovision-style split screen – hangs another emotionally charged canvas: “The Shipwrecked” (1928) by Swiss painter Heinrich Altherr.

This Expressionist oil on canvas plunges the viewer into a scene of human struggle and existential symbolism, but also resilience.

The central figure, tied to the boat by a rope, waves a piece of cloth, as if seeing saviors on the horizon, beyond the painting’s edge. The style is dark, the shadows are deep, and the atmosphere is intense.

Austria sent JJ (full name Johannes Pietsch) to Eurovision, a countertenor displaying operatic vocals fused with electronic beats, in a parallel emotional voyage. “Wasted Love” was staged in stark black-and-white with digital waves crashing around him. The cinematic staging mirrored Altherr’s stormy drama – a man adrift in emotional wreckage, still longing for connection.

The shipwrecked JJ, drowning in the ocean of his romantic feelings, found a lifeline in 436 points (258 from the jury, 178 from the televotes), sealing Austria’s third Eurovision victory.

Saint Gregory (Matthias Stomer)

Matthias Stomer, a Dutch master shaped by the chiaroscuro of Caravaggio, spent much of his artistic life under the patronage of the Italian Church, bringing saints and bible stories to the canvas.

“Saint Gregory” (17th century) is a Baroque portrayal of one of the four great Latin Church Fathers, depicted with a vivid expression and gesture, and surrounded by books. Typical of Stomer’s Caravaggesque style, the painting uses a strong contrast between light and shadow, dramatizing it with the presence of a dove, the Holy Spirit incarnate.

Four centuries later, light once again became scripture on stage, as Ukraine’s Ziferblat brought “Bird of Pray” to the Eurovision spotlight.

The bird symbol, as well as the use of light magic (literally a light-transfer trick between fingertips), appeared central in their performance.

In a powerful staging, a truss of lights hovered over the stage as if it were a bird’s wings, a visual emphasizing migration and survival, the country’s burning struggles.

Ziferblat flew to eighth place at Eurovision.

Portraits of the Zurich Standard-Bearer Jacob Schwytzer and his wife Elsbeth Lochmann (Tobias Stimmer)

Painted in 1564 by Tobias Stimmer, portraits of the Zurich Standard-Bearer Jacob Schwytzer and his wife Elsbeth Lochmann are a fine example of Swiss Renaissance portraiture, exposing the growing self-awareness and status of the Zurich bourgeoisie at the time.

The Zurich banner bearer and granary caretaker stands in a commanding pose, in rich attire that highlights his social standing, pride, and masculine authority. His wife’s portrait is a complementary one, presenting her in elegant clothing, reinforcing the couple’s prestige and wealth.

The decision to become immortal through larger-than-life full-length portraits was bursting with self-confidence, not an ordinary thing in the period.

Fast forward 461 years. Shkodra Elektronike, Albania’s duo that blends traditional music with modern electronic beats, exists in a vastly different artistic context. Still, their Eurovision performance of “Zjerm” mirrored a similar bold authority, care for identity, and a color dichotomy of red and black, representing male and female energies that fit together, yet barely touch, like those twin portraits.

Albania tied with Ukraine for 8th place in the Grand Final, but in terms of commanding presence and aesthetic conviction, they easily stood their own ground – much like the bourgeoisie of Zurich once did, centuries ago.

Warrior with Halberd (Ferdinand Hodler) & The Queen of Sheba’s Visit to Solomon (Jan Davidsz. Remeeus)

“Warrior with Halberd” (1898) is another work of Bern-born painter Ferdinand Hodler in Kunstmuseum Basel’s possession. Depicting a standing warrior in a heroic, sculptural posture, holding a traditional medieval pole weapon, this oil on canvas is an example of Hodler’s series embodying national pride.

With a similar commanding presence, memorable costume(s), and well, a moustache, Australia’s Eurovision warrior Go-Jo (real name Marty Zambotto) tried to win the crowds with his “Milkshake Man” song. The difference is that down under, warriors eventually take off their clothes, and then suggest using different kinds of weapons, those that splatter milk instead of blood. Was that milk, hm?

“The Queen of Sheba’s Visit to Solomon” (early 17th century), painted by Jan Davidsz. Remeeus, also resonates with Go-Jo’s act. A tale of diplomacy, according to a legend, ends up as a romantic relationship that starts centuries of the Solomonic dynasty ruling Ethiopia (learn more about the Aksumite Empire’s myths here).

Simply put, all roads lead to a giant high-speed blender, a materialized thirst trap, where you’ll bow because he “can tell you want a taste of the milkshake man”.

Despite his charismatic magnetism and energetic performance, Go-Jo narrowly missed a spot in Eurovision’s Grand Final, finishing 11th in his Semi.

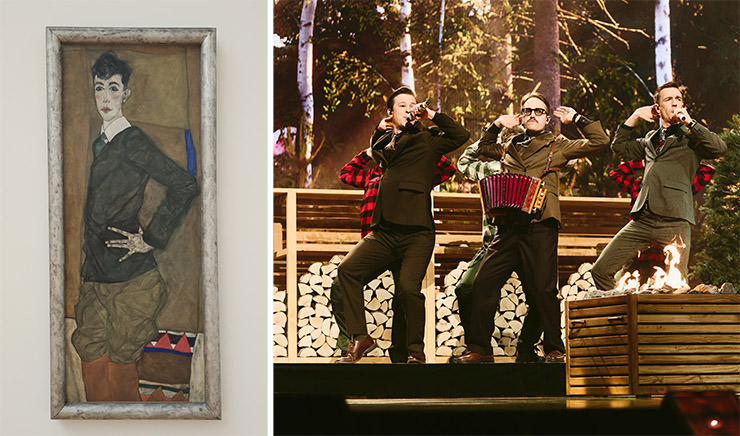

Portrait of Erich Lederer (Egon Schiele) & The Bath at Leuk (Hans Bock the Elder)

Egon Schiele’s “Portrait of Erich Lederer” (1912-1913) is a masterclass in Viennese Expressionist portraiture. This oil on canvas is presented in a long vertical format, highlighting the subject’s stature.

Erich, the son of August Lederer, a major patron of Gustav Klimt, who introduced Schiele to the family, has piercing eyes, gazing at the observer, with a hand confidently resting on his hip. Contrasted by his formal attire is Erich’s aristocratic, pale skin. He could almost be Scandinavian.

And he is perfectly dressed for the sauna, at least if we ask the fully buttoned-up KAJ, Sweden’s representatives on the 2025 Eurovision. Their entry, “Bara Bada Bastu” (translating loosely as “Just Take a Sauna”) was performed as a wild, sauna-themed spectacle, which they executed in very formal attire.

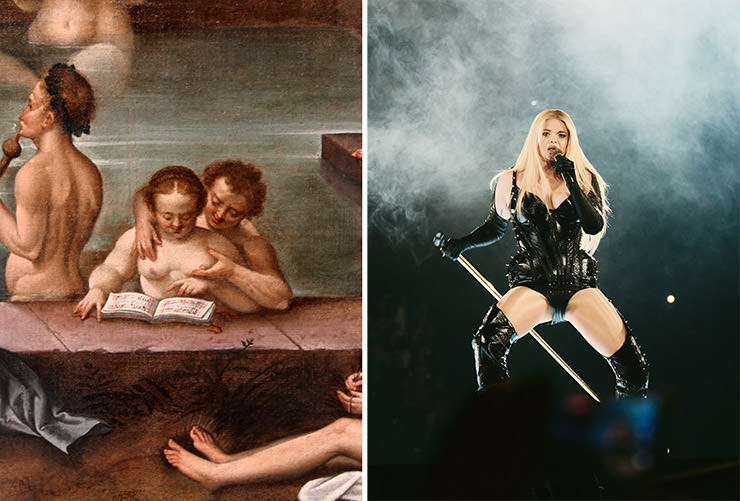

“The Bath at Leuk” (1597), possibly inspired by Leukerbad, a famous Swiss thermal spa, and one of the most famous wild baths of the period, is Kunstmuseum’s art piece celebrating a popular pastime that combines hygiene, relaxation, socializing, and entertainment.

German painter Hans Bock the Elder showcased men and women bathing, gossiping, and even flirting together. In a place bustling with naked bathers, just like in “Bara Bada Bastu”, three fully clothed (we could even say – overdressed) men observe the scene.

The first Finnish act to represent Sweden managed to secure a steamy fourth place at Eurovision.

The Bath at Leuk (Hans Bock the Elder) – again

Let’s not towel off “The Bath at Leuk” just yet. After all, if Swedes were singing about a sauna, these were Finnish Swedes singing about – Finnish sauna.

Finland proper sent Erika Vikman to Eurovision, a pop provocateur who brought a different kind of heat.

Her entry “Ich komme” (“I’m Coming”) leaned hard into sexual innuendo – so hard, in fact, that Eurovision’s official site politely translated the lyric “grab my ass” into a more palatable “hold on to me tight”. Costume modifications were also requested from Erika: apparently, there are limits to how much thigh Europe can handle at 9 pm.

Similarly, “The Bath at Leuk” with its nude interacting visitors was deemed too controversial when Kunstmuseum acquired it in 1872. Subtle erotic allusions to what’s really going on in public baths were too much for puritan Baslers. The painting was initially gathering dust in the conservator’s office.

Art is speaking about true life, and sometimes it’s about seeking sensual pleasures. Sooner or later, it comes in front of consumers.

Erika came in 11th place, but true Eurovision fans know that some acts, like certain paintings, are too bold to be measured by placement alone.

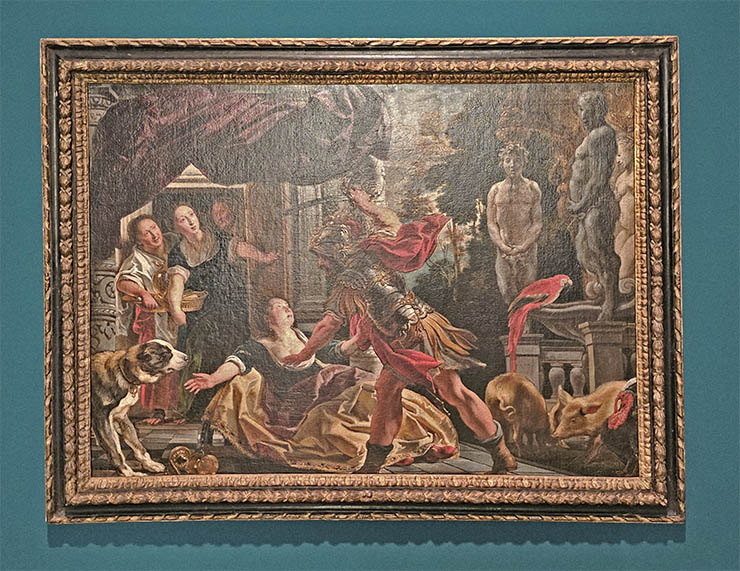

Ulysses Threatening Circe (Jacob Jordaens)

Finland wasn’t the only country to ruffle Eurovision’s moral feathers this year. Malta’s Miriana Conte was forced to rename her provocative track from “Serving Kant” to just “Serving”, so its explicit-sounding pronunciation wouldn’t upset sensitive ears.

But where were we in Kunstmuseum Basel? Ah, yes, “Ulysses Threatening Circe” (1630-1635)…

We have a dramatic Baroque painting from Flemish artist Jacob Jordaens, capturing a critical moment from Homer’s “Odyssey”. Ulysses (Odysseus) stands above Circe with a raised sword, commanding her to reverse the spell on his men. It is Circe’s magic that turned them into pigs, visible in the bottom corner.

Much like the mythical sorceress, Miriana Conte complied with the rules to stay in the game. She trimmed her lyrics that provoked otherwise blameless individuals, making them grunt and oink. Hopefully, they didn’t watch that sensual choreography of the final performance.

In a struggle between power and magic, pure force might have won, but this didn’t stop the audience from filling in the gap in the song’s magic potion formula, loud and clear. Hear how it sounds when you don’t mute your audience – Arena Plus attendees serving “Kant” in this YouTube short!

Malta’s result in Eurovision’s Grand Final was 17th place, but Miriana remained undefeated. Diva not down!

Malta is sinking. Check out the things to do in Malta while you can!

The Death of Pietro Aretino (Anselm Feuerbach)

“The Death of Pietro Aretino” (1854) is the kind of painting that screams: “What the hell just happened?” The Italian Renaissance poet, known for his biting wit and scandalous verse, is shown collapsing backward at a feast – a dramatic exit!

German painter Anselm Feuerbach had grand hopes that the Prince Regent would buy the painting for the Karlsruhe collection, but the Acquisition Commission bluntly rejected it. “The regent is just a child in art matters”, disappointed Feuerbach wrote.

On Eurovision, Princ (not Regent, real name Stefan Zdravković) represented Serbia with “Mila”, a ballad mourning an unrequited love. The lyrics invoked the imagery of the last supper and a descent into the arms of Hades, as the protagonist was left with only memories for Mila, who “brought life back from the edge”.

In a dramatic Eurovision staging, the long-haired Princ echoed Aretino’s fragile posture, taking a theatrical nosedive. The dancers dragged him across the floor, which highlighted his surrender to personal tragedy. It also made the cleaning crew’s job easier, with one less performer to mop up after.

Despite the impassioned performance, Princ didn’t manage to impress Eurovision’s own Acquisition Commission in the Semi-Final. “We gave our all, I left my heart on stage, and I hope you felt it”, Princ commented.

Play of the Nereides (Arnold Böcklin)

“Play of the Nereides” (1886) is another oil on canvas from Kunstmuseum’s unofficial “What the hell just happened?” collection.

The Swiss symbolist Arnold Böcklin, fittingly Basel-born, produced a dreamlike aquatic scene, populating it with nymphs, mythological sea creatures. The Nereides twist and twirl in the waves as an image of freedom, vitality, and untamed beauty.

The girl group Remember Monday (UK) brought a similarly vibrant whirlpool of energy to the Eurovision stage.

Their genre-bending “What the Hell Just Happened?” delivered cascading harmonies, fluid, synchronized, and dynamic like Böcklin’s nymphs.

Equally playful and with expressive gestures, Lauren Byrne, Holly-Anne Hull and Charlotte Steele might have made us all remember Monday, but also helped us forget Saturday. In the Grand Final of Eurovision, the public awarded them a neat nul points. Fortunately, the jury threw them a lifebuoy: 88 points, enough to keep them from sinking to the bottom of the scoreboard. They finished 19th.

Children Making Music Overheard by a Nymph (Anselm Feuerbach)

Another of Feuerbach’s classicist masterpieces, “Children Making Music Overheard by a Nymph” (1864), depicts youngsters playing a string instrument, unaware of the presence of a curious nymph lurking beyond the trees.

It’s a pastoral daydream – myth meets musical innocence – wrapped up in Feuerbach’s romanticized realism and fascination with classical art.

Representing Feurbach’s homeland, Germany, a young sibling duo, Abor & Tynna, brought a fresh, urban sound to Eurovision with their infectiously rhythmic song “Baller”. It’s still about being watched while making music – this time by Europe and half the internet instead of a nymph.

They also paid homage to their classical upbringing, coming up with an act that fused modern electro-pop with cello riffs.

“Ich ballalalalalalaler Löcher in die Nacht” (“I shoot holes into the night”) might not make complete grammatical sense, but Europe found it weirdly hypnotic. Much like Feuerbach’s nymph, they couldn’t help but peek in.

Germany’s shot landed in a solid 15th place in the Grand Final.

Death and the Woman (Hans Baldung Grien) & Untitled (There is no more unfortunate being under the sun than a fetishist who longs for a woman’s slipper and has to make do with a whole woman, K.K.: F) (Rosemarie Trockel)

“Death and the Woman” (1520-1525) shows a decaying skeletal figure firmly gripping a terrified woman from behind. Once it arrives, death is inevitable, and clinging.

The theme of mortality was very common in Hans Baldung Grien’s oeuvre. This German Renaissance artist frequently depicted a grotesque personification of death next to young women, warning against the transience of life and worldly pleasures.

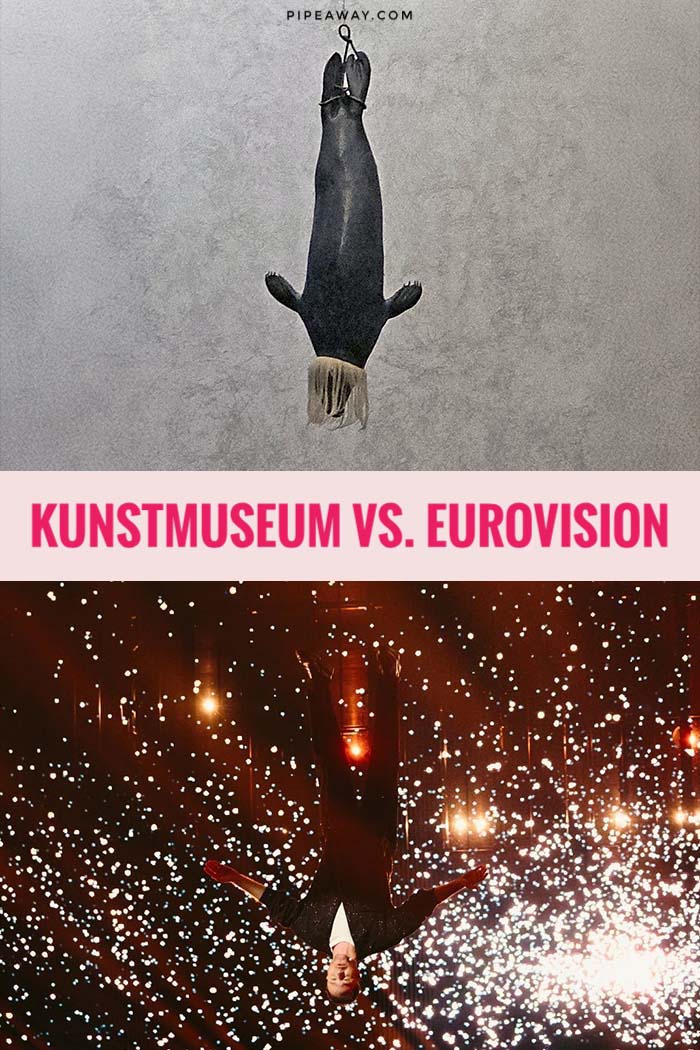

“How Much Time Do We Have Left”, Klemen Slakonja asked exactly five centuries later. His wife, actress Mojca Fatur, was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer. The question eventually became a song about shared vulnerability, representing Slovenia at the 69th Eurovision Song Contest in Basel.

Klemen’s touching performance had a minimalist yet powerful staging. In one moment, he embraced his personal emotional collapse literally, and sang suspended upside down for thirty seconds. Perhaps a nod to life turned on its head, or to the art of holding on when the world flips.

As I descended to the underground passage in order to get to the Kunstmuseum Basel extension (Neubau), a hanging seal suddenly felt familiar. The unnamed work by German visual artist Rosemarie Trockel actually had quite a long title that quoted Austrian satirist Karl Kraus: “Untitled (There is no more unfortunate being under the sun than a fetishist who longs for a woman’s slipper and has to make do with a whole woman, K.K.:F)” (1991).

Suspended by its hind legs on a chain, as if it’s dragged aboard a ship, the seal’s inverted posture referenced brutal hunting practices. The bronze animal wore a synthetic-hair collar, possibly symbolizing consumerism, the human desire to possess everything that surrounds us.

From Baldung’s bony embrace to Trockel’s brutal suspension, from a deathly grip to a life upside-down – these works remind us that art confronts.

Klemen’s song, with just 23 points, was sadly left hanging in the Semi-Final.

Portrait of a Woman: Saint Catherine (Lucas Cranach the Elder)

Lucas Cranach the Elder, a leading artist of the German Renaissance, created several portraits of Saint Catherine of Siena, an Italian mystic, influential theologian, ascetic, and stigmata. Cranach emphasized her devotion, wisdom, and martyrdom, aligning with Reformation-era ideals.

A notable example is a half-length “Portrait of a Woman: Saint Katherine” (1508), depicting a young woman in a prayer, dressed in black attire with a traditional Dutch bonnet. Her expression is serene, highlighted by soft contours and delicate shading.

I’m not sure what was the thing that Nina Žižić wore while performing her Eurovision entry for Montenegro. After a walk through Kunstmuseum Basel, the best match I could find was this Dutch cap worn by Saint Catherine.

With “Dobrodošli” (“Welcome”), Nina did appear like a martyr; she even had a bruise on her forearm, probably a bit more discreet than Catherine’s wounds of Christ. Blindfolded, Nina could’ve also potentially been a goddess of justice, encircled by an aura of a gigantic white pillow.

If not a martyr herself, Nina at least sang to them: “Put a smile on your face, endure it all, it’ll pass.”

Montenegro had to endure just 12 points from the televotes, thus finishing last in Semi-Final 2.

Phallic Shoe (Yayoi Kusama)

Besides recognizable repetitive polka dots, Yayoi Kusama’s artistic world is covered in phallic shapes. What started as a personal fear of sex continued as an artistic obsession with phalluses.

Encased in a glass box like a possibly cursed Cinderella relic, “Phallic Shoe” (1966) is a soft sculpture, basically a high-heeled shoe filled with phallic forms (as precise as it gets when the author suffers from phallophobia, and just possibly – potatophilia). Japanese artist aimed to make this object a symbol of male fantasies and female anxieties.

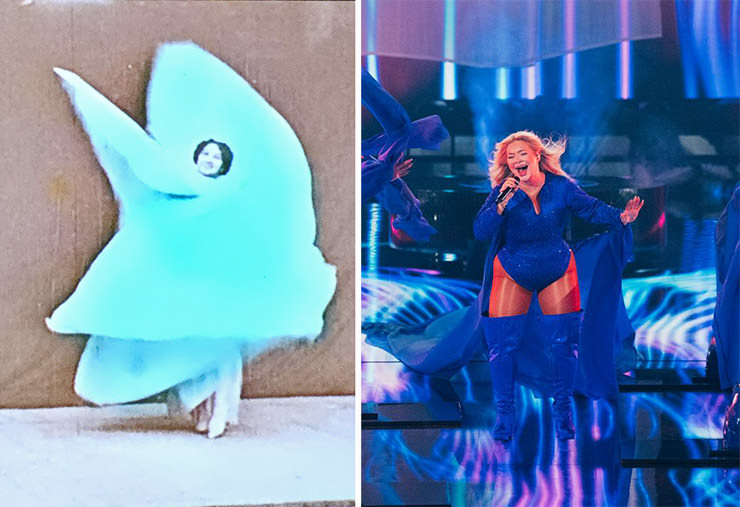

Topics of fashion and societal expectations collided in the Eurovision performance of Justyna Steczkowska for Poland. Her song “Gaja”, celebrating the goddess of Earth and possibly Westeros, unfolded through a very dynamic dance choreography. Three out of four performers were men, and yet all of them wore extremely high heels.

Coming from the possibly least LGBTQ-friendly EU country (ranking just slightly better – or less worse – than Romania), Justyna’s artistic proposition managed to confuse as probably the gayest-looking act of Eurovision 2025 (that’s gayest as in gay, not Gaja).

Maybe that’s the combo of fear and fascination Kusama talked about, a thin, permeable line that separates homophobia from homo-desire.

Skilled in stilettos, Poland ran to the 16th place in Eurovision’s Grand Final.

Film Lumière n˚765, 1 – Danse serpentine, II (Anonymous)

Next, I entered a room where an early cinematic work by Louis and Auguste Lumière was projected on the wall. “Film Lumière n˚765, 1 – Danse serpentine, II” (1897-1899) captures a dance style popularized by Loïe Fuller, an American Symbolist performer known for her flowing fabric movements and innovative stage lighting.

The dancer twirled her voluminous semi-transparent robes, creating hypnotic, fluid shapes that constantly changed colors. Of course, we cannot witness the entirety of the craze the Butterfly-woman caused in Paris music halls, simply because of the limits of the first cinematograph, which recorded moving images in black and white. But in this version, Lumière brothers hand-colored the film frame by frame, letting us imagine the kaleidoscopic euphoria the novelty performance unleashed on Belle Époque audiences.

More than a century later, Denmark’s Sissal also aimed at delivering a hypnotic theatrical experience at Eurovision 2025 with her song “Hallucination”.

There were no color changes in the Danish dreamlike blue universe. But Sissal did use a wind machine to whip her long translucent train into a fluid sculpture of air, as well as surreal effects provided by her moon-booted dancers executing gravity-defying lean moves.

Though some considered Denmark a dark horse for a surprise victory, Sissal was eventually wind-swept to 23rd place on the scoreboard.

Motorboat (Gerhard Richter)

At first glance, “Motorboat” (1965) appears to be a blurry black-and-white photograph, until you realize it’s an oil painting. Part of the New European Painting art movement, this figurative painting is, however, based on a real photograph, originally used in an ad for Kodak Instamatic camera.

German visual artist Gerhard Richter is known for blending realism with abstraction by using a photo-painting technique. He deliberately softened the image of a group of people enjoying a ride on the boat. This way, he created a sense of movement and fleeting moments, as well as stimulated an exploration of memory and perception.

On the Eurovision stage, an equally joyful ride was delivered by Iceland’s sibling captains called VÆB. With “RÓA”, brothers Matthías Davíð and Hálfdán Helgi Matthíasson rowed their pop-electronic vessel through a nautical fantasy.

A cheerful group of friends cruised through an uplifting sea adventure that combined the action on stage with visual effects added for at-home audiences.

While they easily navigated through the Semi-Final (finishing 6th), VÆB’s boat sank to the 25th (second-to-last) place in the Grand Final.

Large Mold Picture (Dieter Roth)

Dieter Roth was a Swiss artist who didn’t just think outside the box – he fermented it. Famous for using organic materials like chocolate, yogurt, and bread, Roth embraced decomposition and decay as part of the creative process.

His “Large Mold Picture” (1969), exhibited at Kunstmuseum Basel, is exactly what it sounds like: a layered sandwich of moldy matter sealed between glass panels. It’s art that evolves with fungal blooms, reminding us of the ephemeral nature of nature. Technically, it is a moldy mold of mold.

Similarly unconventional Marko Bošnjak, who represented Croatia at Eurovision 2025, also brought something that wasn’t easy to digest. His song “Poison Cake” was a haunting, metaphor-heavy tale of vengeance served dark and cold.

You don’t hear songwriters framing revenge as their central theme that often. Let’s just say that poisoning someone as a method of retaliation is a demon typically left unsung.

While Roth’s work was sometimes dismissed as messy, and many struggled to see its artistic value, Bošnjak also polarized the audience, struggling to fully connect with Eurovision juries and the viewers. Despite delivering a passionate performance, Croatia didn’t qualify for the Eurovision final.

If Marko could learn something from Dieter, the lesson would be that bold and boundary-pushing art pieces ripen with time. Or rot. Sometimes, it’s all the same.

Not all Croatian cakes are there to poison you. Take a look at the recipe for Rab Island's delicacy - Rapska torta!

Aetas aurea (Medardo Rosso)

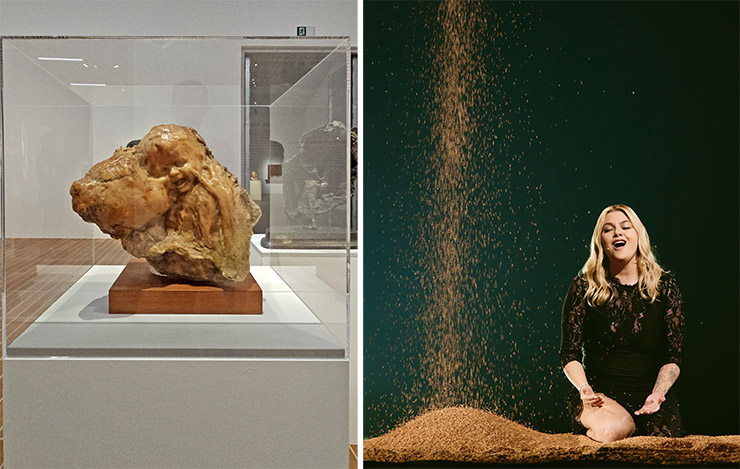

“Aetas aurea” (1886), Latin for “The Golden Age”, is a wax sculpture that portrays a mother with a son in an intimate moment.

Italian sculptor Medardo Rosso, who moved to Paris, where he befriended and influenced Auguste Rodin, the father of modern sculpture, used his own wife Giuditta Pozzi and son Francesco as models for this double portrait.

The mother is kissing the boy, their faces in a tender embrace, melting into each other. It’s an image of maternal love and unity, a utopia of perfect happiness, as the title suggests.

For this “Aetas Aurea”, Rosso chose an unusual medium – wax. Unlike traditional marble or bronze, this material reinforces the idea of fragility and the fleeting nature of the moment.

Louane from France knows all about the ever-shifting sands of time slipping through one’s fingers. For “Maman”, a heartfelt ballad dedicated to her late mother, the French Eurovision act brought a real sandstorm to the stage, adding to the intimate story of grief, healing, and motherhood.

Unlike the Polish act, Louane performed her song barefoot, in a simple black dress, putting an accent on her raw, powerful vocals.

France placed 7th in the Grand Final.

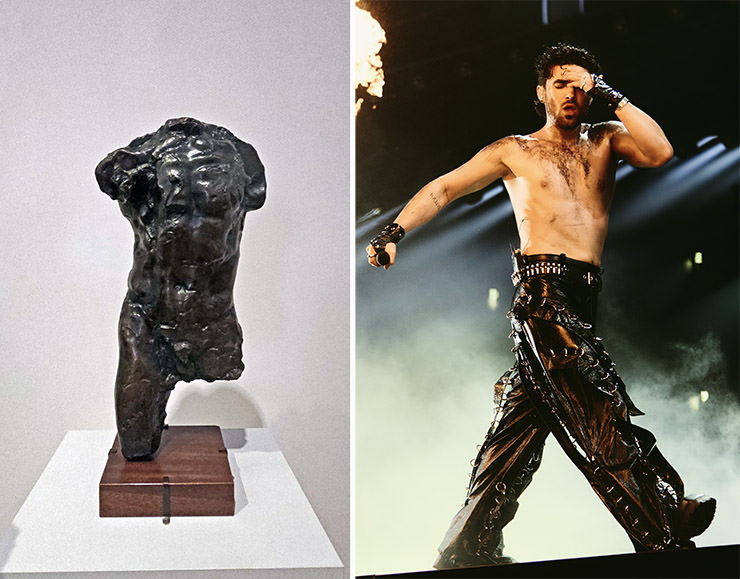

Torso of the Walking Man (Auguste Rodin)

Auguste Rodin wasn’t just Medardo Rosso’s friend or rival; he admired the work of the innovative Italian sculptor. It’s fitting, then, that the special exhibition “The Invention of Modern Sculpture” in Kunstmuseum’s new building brings the two together. Alongside Rosso’s “Portrait of Henri Rouart” (1890) and Cézanne’s “Five Bathers”, Rodin’s “Torso” (1878-1879) is shown.

This torso from the study for Saint John the Baptist, also known as “Torso of the Walking Man”, is one of Rodin’s best-known compositions. Over two decades, he would work on transforming this rough-surface, fragmented bronze sculpture, detached from its arms and head (it was Saint John after all!). It is raw, muscular, and gloriously incomplete, embodying movement more powerfully than most whole statues ever could.

Swiss Eurovision had its own walking man with a missing upper wardrobe – PARG a.k.a. Pargev Vardanian from Armenia. Shirtless, just smeared with some black paint, brimming with primal energy instead of adhering to classical perfection, the singer marched across a giant treadmill during his performance of “Survivor”. It’s the closest a human could get to being static like a sculpture, yet in motion, like Rodin’s sculpture.

“I’m a survivor, stay aliver, do or die in my prime”, our moving torso sang, emphasizing themes of struggle. Struggle with English included.

Armenia walked (and walked and walked) to the 20th place in the Grand Final.

Fire (A. R. Penck)

A. R. Penck (born Ralf Winkler), a leading voice of German Neo-Expressionism, forged a peculiar visual language that recalls primitive art normally seen in caves.

“Fire” (1967-1968), oil on canvas, brings his signature Standart figures (simplified, stick-like forms) that symbolize universal human struggles.

Fire is often present in Penck’s work, as an element of destruction, transformation, and renewal – a reflection of his experiences growing up in divided Germany, during the Cold War.

Norway’s Kyle Alessandro started his fire on the Eurovision stage with “Lighter”, a flammable song that combines pop, baroque, and folk sensibilities. Dressed in metallic armor, symbolizing his strength and resilience, the artist explored the themes of self-reliance and overcoming adversities, following the advice received from his cancer-diagnosed mother: “Never lose your light!”

Despite the energetic stage presence that received a warm reception at the venue (those flame projectors help!), Kyle finally ranked 18th at Basel Eurovision.

Die Mütter (Käthe Kollwitz)

“Die Mütter” (1921-1922) or “The Mothers” is Käthe Kollwitz’s powerful black-and-white woodcut from her “Krieg” (“War”) series. Seven woodcuts were created in response to the catastrophic impact of World War I, and as a resistance act against Germany’s culture of military sacrifice.

The artist’s piece doesn’t just reflect her deep pacifist convictions, but also a personal grief. She lost her younger son, Peter, on a battlefield in Flanders, in the early months of the war.

The composition forms a protective wall of mothers, women united in shielding their children in a tight defensive circle, refusing to give them up to future wars. This activist work condemns militarism and the glorification of sacrifice.

Now, Claude Kiambe, who represented the Netherlands at Eurovision, arrived in the country as a refugee, fleeing from the political unrest in his homeland, the Democratic Republic of Congo.

His emotionally soaked song “C’est la vie” was an ode to his mother, a woman who shielded her children to secure them a future of better possibilities. Life is unpredictable, but one should embrace it, his mother’s advice said.

The juries embraced Claude’s message, but televoters were more reserved, giving him just 42 points. He landed in 12th place overall. Well, c’est la vie.

KUNSTMUSEUM BASEL INFO Kunstmuseum Basel address Hauptbau – the main building: St. Alban-Graben 16 Neubau - the new building: St. Alban-Graben 20 Gegenwart - the contemporary art building: St. Alban-Rheinweg 60 Parking near Kunstmuseum Basel Kunstmuseum Basel has its own underground car park that can fit 350 vehicles. It’s located at Luftgässlein 4. The basic price for the parking is CHF 3 per hour. Opening hours Monday: closed Tuesday-Sunday: 10 am – 6 pm Wednesday: 10 am – 8 pm How long do you need for Kunstmuseum Basel? A visit to the Kunstmuseum Basel typically takes 2 to 3 hours, depending on how deeply you want to explore its vast collection. If you're an art enthusiast, you might want to spend half a day in museum’s three buildings, to fully appreciate the masterpieces spanning from the 15th century to contemporary art. The historical collection is housed at the Hauptbau, special exhibitions and art from the collection after 1950 at the Neubau, while contemporary art from 1960s onwards can be found at the Gegenwart. Kunstmuseum Basel ticket price Adults 20 years and older: CHF 25 Students: CHF 12 Teenagers: CHF 12 Children: free entrance With Basel Card: CHF 12.50 On working days, the last operating hour is happy hour at Kunstmuseum Basel. This means you can visit its main collection free of charge on Tuesday, Thursday and Friday from 5 to 6 pm, as well as on Wednesday from 7 to 8 pm. Free entrance at Kunstmuseum Basel is also available every first Sunday of the month. Want to save even more? Check out these free things to do in Basel!

Chasing Eurovision among the Kunstmuseum Basel artworks – Conclusion

Eurovision 2025 took over Basel for a week. But some of these performances had a longer-lasting potential. So we moved the contestants into the Kunstmuseum, the world’s oldest public art collection.

Not every act may pass the test of time. Some will fade into the fog of forgotten Grand Finals. Others might be debated for years.

Whether displayed on a museum wall or broadcast on Europe’s flashiest stage, art can be emotional, provocative, and occasionally misunderstood by the general public

From Kusama’s phallic heels to Rodin’s walking torso, from barefoot ballads to moon-booted hallucinations, each performance found its artistic twin among the museum’s paintings and sculptures.

These Eurovision-Kunstmuseum pairings might not be perfect soulmates. But there’s something to learn from connecting the dots in this cultural crossover: Whether displayed on a museum wall or broadcast on Europe’s flashiest stage, art can be emotional, provocative, and occasionally misunderstood by the general public.

One person’s ‘meh’ is another’s masterpiece. Sometimes, it takes centuries to validate the votes given to any artwork. So only time will tell whether this year’s Eurovision stories were worth framing.

Some acts missing? Explore Kunstmusem Basel artworks by yourself, and make your own perfect pairs!

Liked the article on Eurovision-museum match-ups? Pin it for later!

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning if you click on them and make a purchase, Pipeaway may make a small commission, at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our work! The authors of all photographs are mentioned in image titles and Alt Text descriptions. In order of appearance, these are: Ivan Kralj - photographs of all Kunstmuseum Basel artworks and museum's gift shop Sarah Louise Bennett / EBU - Lucio Corsi, Tautumeitas, Red Sebastian, Shkodra Elektronike, KAJ (II), Miriana Conte, Nina Žižić, Sissal, VÆB, Kyle Alessandro Alma Bengtsson / EBU - Eurovision alphorns, Yuval Raphael (I), Ziferblat, Go-Jo, KAJ (I), Erika Vikman, Princ, Remember Monday, Abor & Tynna, Klemen, Justyna Steczkowska, Marko Bošnjak, Louane, PARG, Claude Corinne Cumming / EBU - Melody, Tommy Cash, Zoë Më, Yuval Raphael (II), JJ